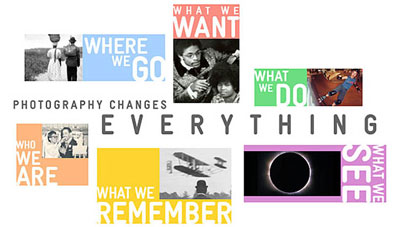

Photographs change the way we behave, look at the world and — most importantly — treat other human beings. If you want to know more about what makes a photo work and about the power of photography, then you might want to have a look at the excellent book Photography Changes Everything by writer and curator Marvin Heiferman whose Twitter handle whywelook says much about the wide-eyed, varied and in someways irreverent approach of Heiferman to the world of imagery. The book ponders the question of how we see. What’s a photograph? How does it work? Of course no book is exhaustive, but Heiferman gives you a pretty good idea of photography’s relevance and beauty.

Heiferman’s collection of essays does not attempt to be an all encompassing philosophical tome about photography’s purpose and uses. Still, it’s a must-read to get a more profound handle on how photography can change things.

We’re living in a world of infotainment. We have no time to read. Increasingly, images convey the message. The image replaces text. Because everyone is looking. The sheer number of images being generated is part of what people are trying to figure out. The numbers keep changing, but the latest figure is that 1.2 billion photographs are made per day. Half-a-trillion per year. One needs to understand this volume of imagery just to navigate the world, says Heiferman:

We trust so many pictures, we distrust so many pictures that we need to take a step back from the taking of and looking at of photos and think more of how it works in the broadest possible way.

In an extensive interview with Wired about this “universal language” called photography, the former Smithonian consultant goes into great detail about the exploding photography market. Images are all all around us and used in ways we don’t even consider. Yet, photography isn’t really a universal language; it’s multiple languages, says Heiferman. The dialogs you can have with neuroscientists about photographic images are as interesting and as provocative as the dialogs you can have with artists.

Or ever wondered if there is a difference between looking at a thing and looking at a photograph of that same thing? Heiferman:

Why is a photograph powerful besides just recognizing in the image, what neurologically connects this thing you look at on paper or on screen to what’s in your head. Those are really big issues when trying to figure out photography’s power. What is the power of images in terms of our psychological response to them? What images make you want to buy something, fuck something, vote for something?

However, photography changed drastically since and today there’s so much image manipulation available. Is it a photograph when you say it is? Or going even further: today’s photography that anyone can afford, is it a democratic medium? Heiferman:

It is non-democratic in the sense that the kind of images we make are always at the whims of manufacturers we make them with but still it’s pretty extraordinary if we think of the power it puts in peoples hands — look at citizen journalism. It’s totally changed the way we operate.

Heiferman makes photography sound as consequential as did Michael Fried’s Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before.

Photography matters. Still, photographs never have a single meaning; neither does photography as a whole. Photographs are open questions. And that’s part of the medium’s power and beauty.

You can order “Photography Chances Everything” from Amazon.

More on Heiferman’s earlier Smithonian project click! in this video: