There is practically no Internet photo site on which the term is not thrown around, but oddly enough, I have never seen it defined. Yes, I see various cameras labeled “pro cameras,” either by marketers or by owners who want to be thought of as “pros.” But I have not a clue what constitutes a “pro camera.” Is it a laptop tethered, 50MP, autofocus Hasselblad or other medium format camera? Is it a top-of-the-line Nikon or Canon “full-frame” — and what does that mean? DSLR? Is it a Leica digital M that costs upwards of $10k but cannot be taken out on a damp day without risking frying it? Is it a camera that can shoot at 12 frames per second? Or might be all of those and none of them?

I would suggest that the only camera that should be called a pro camera is a camera used by a photographer who either earns a substantial portion of his or her income from photography, or, alternatively, any photographer who produces professional quality work. And that would include any camera used by such photographers. After all, they are “pros,” and so their cameras are “pro cameras.”

I recall reading some years ago that a well-known photographer whose name escapes me at the moment was using Canon Rebel bodies in Iraq, because they were far lighter than the EOS 1 elephants, and they were inexpensive enough so that if they failed, he could just toss them and replace them without having to take out a second mortgage on his home. And the real point, of course, was that mounting good glass, those bodies could do everything he needed them to do; they were “pro cameras.”

I also remember that another photographer went to Iraq with a pile of small Olympus fixed lens cameras with swiveling LCD screens. He’d hand two around his neck and when he needed to shoot a sequence, he’d shoot them in sequence. Again, like the Rebel fan, he did it because they were small, light and relatively inexpensive. And they produced images with which he was happy.

When we talk about pro cameras today, we seem to forget that there was a time when 35mm cameras were dismissed as “toys,” when newspaper and magazine photo editors insisted that their photographers shoot with “real” cameras, which then meant Speed Graphics and, in a pinch, Rollei 2 1/4s. 35mm film just couldn’t possibly produce professional quality images, these editors insisted. Sounds familiar?

And keep in mind that when Cartier-Bresson, Eugene Smith and Robert Capa were shooting with Leica and Contax 35mm cameras, the glass was close to atrocious, and the film stocks they were using couldn’t produce images that compare in technical quality to those produced even by some point-and-shoot cameras today. Yet we revere their work, which hangs in the world’s leading museums and sets standards to which today’s professional photographers aspire. Are the images “sharp?” Not if examined at all closely. Is the micro contrast good? The what? You get my point I’m sure.

The reality is that most photographers today, including most professional photographers, do not need all the bells and whistles –- and capability — of the top-of-the-line “pro cameras” produced by the leading camera manufacturers. And neither do most of those for whom photography is an avocation rather than a vocation. My son, who happens to be a leading professional skateboard photographer — yes, there are such things — shoots incredible images without owning a “top-of-the-line” DSLR.

In fact, when he shoots skateboarders suspended in midair performing seemingly impossible maneuvers, he often does so using manual focus rather than autofocus, and he sometime makes the shots with an old film Hasselblad without a motor. How? He’s a pro.

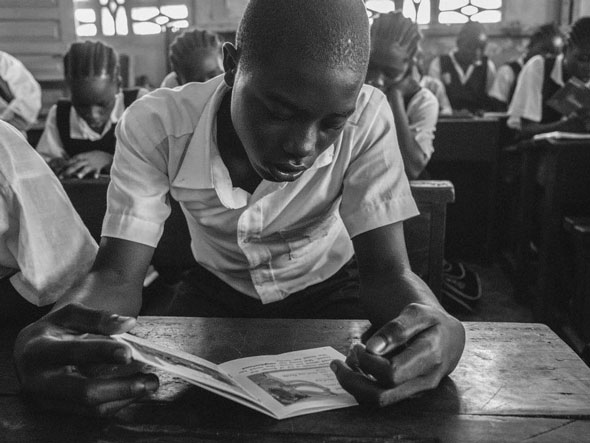

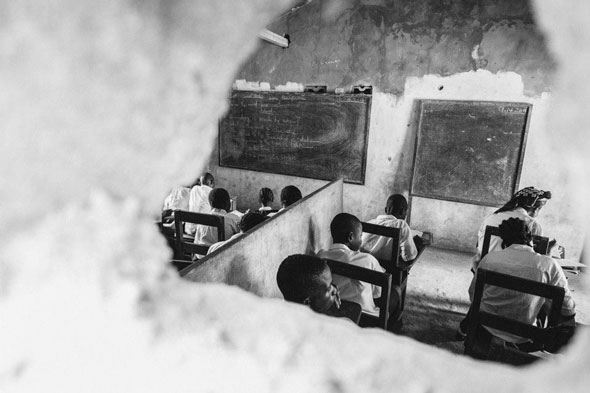

I have been teaching documentary photography at MIT for 13 years now, and I shoot professionally. I just came back from two weeks of teaching and shooting in Liberia. Yet since leaving the world of film and my Leica M6s a decade ago, I have not owned a single “pro camera.” I did all my work in Liberia with a Fujifilm X-Pro1, an X100s and an Olympus OMD-EM1 — a Micro Four Thirds camera.

Why? Because all three cameras together meet my needs. Because I could carry all three around my neck and shoulders all day without killing myself. Because they all have great glass. And because they give me terrific image quality that I can easily have printed up to 20×24″ if I want to, and displayed on the Web will compare to anything out there.

You can see a gallery of black-and-white images here — and color ones here. I would suggest that shooting with “pro cameras” would not have improved them, although in a few of them, using the latest generation of Leica aspheric glass might have reduced some of the flare.

The bottom line? The only camera or cameras you need are those cameras that will meet your needs. Yes, if you are shooting for magazines you might well need a digital camera with a sensor the size of the film in what once were considered “toy cameras.”

If you are shooting Olympic diving or ice dancing and need sequences, you may well need a “pro body” to get high speed sequences.

Otherwise? Shoot like a pro, and you will be shooting with a “pro camera” – even if you are using an iPhone.