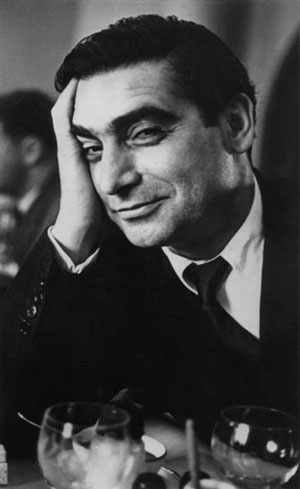

Expelled from Hungary at the age of 17, Endre Friedman bounced from Germany to France learning photography along the way. When he arrived, the man we know as Robert Capa was born. Possibly the greatest war photographer in history, Capa’s contributions are as broad as his interests.

Understandably upset Capa went to Germany to complete his education until Hitler’s role forced him to move on. Finally settling in Paris, Capa met the love of his live Gerda Taro, who was working as a photo assistant. The combination of her creative marketing and Capa’s photographs soon solidified his role as a serious photographer. The two of them created the identity of Robert Capa. It had a good ring to it and Taro spread his images all over town, talking up his genius to the photography editors. Even after they were confronted for fraud, it was too late. The not so famous Endre Friedmann had successfully established himself as a prominent photographer of the Spanish Civil War. This is one of my favorite stories of positive thinking. He wanted to be a photographer, so he declared himself one.

In a 1947 interview, Capa explained why he changed his name:

I had a name which was a little bit different from Bob Capa. The real name of mine was not too good. I was just as foolish as I am now, but younger. I couldn’t get any assignment. I needed a new name badly… And then I invented that Bob Capa was a famous American photographer who came over to Europe and did not want to bore French editors because they did not pay enough… So I just moved in with my little Leica, took some pictures and wrote Bob Capa on it which sold for double prices. (WNBC, October 20, 1947)

The stories of Capa’s life are incredible. If you have not read a book on Capa I would absolutely recommend it. My favorites are Slightly Out of Focus, Blood and Champagne and John Steinbeck’s A Russian Journal with Capa’s photographs. To give you a sense of Capa’s sense of humor, here is a letter he wrote to Ingrid Bergman, asking her out to dinner.

Subject: Dinner. 6.6.45. Paris. France

To: Miss Ingrid Bergman

- Part I. This is a community effort. The community consists of Bob Capa and Irwin Shaw.

- Part II. We were planning on sending you flowers with this note inviting you to dinner this evening- but after consultation we discovered it was possible to pay for the flowers or the dinner, or the dinner or the flowers, not both. We took a vote and dinner won by a close margin.

- Part III. It was suggested that if you did not care for dinner, flowers might be sent. No decision has been reached on this so far.

- Part IV. Besides the flowers we have lots of doubtful qualities.

- Part V. If we write much more we will have no conversation left as out supply of charm is limited.

- Part VI. We will call you at 6:15.

- Part VII. We do not sleep.

You have to give the man credit for asking out one of the world’s most famous movie starlets with a letter. How did it turn out? He got the date and maintained a long relationship with Bergman. The common belief is that Capa never fully recovered from his previous girlfriend Gerda Taro’s death in the Spanish Civil War. While riding on the side of a truck she was side-swiped by a tank. People said Capa was never the same after this. His distance from intimate relationships most likely accounts for why he never married and continued to put himself in the most absurd war scenes imaginable until his death in Indochina.

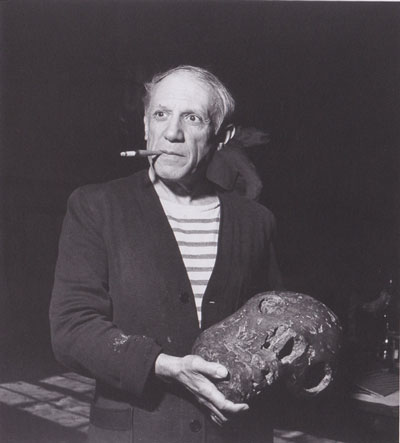

Capa’s Strengths

How can we use the images of a world class war photographer to take better pictures? What simple lessons lie between the frame lines of Capa’s pictures that we can study, replicate and combine into our personal styles?

- Simple Diagonals: Capa worked in both 35mm and square medium formats. Unlike Cartier-Bresson, who was educated formally in art, Capa’s work is less complex. The basic design of 90% of Capa’s images were conceived on a single diagonal. While some of the pictures fit into the 1.5 and Root 4 grids, they were not a part of Capa’s working language. But as we will see, sometimes a successful picture works simply because no one else was there to take the shot. If only one line is used in a composition, we will see how Capa organized off of the diagonal to move our eyes through the scene.

- Figure-to-Ground Relationship: What is this you ask? Figure-to-ground relationship is the term used to talk about how your subject relates in value of the scene or ground. It’s like making a black dot on a white background or a white dot on a black background. This is a primary design tool used throughout human history. If you would like an example think of the design of a Greek vase. The terracotta figures on a vase are light in value against a black glazed background. If we want our pictures to have carrying power they need to be clear. Artists put a light figure on a dark ground or a dark figure on a light ground. Sound simple enough, right?

- Highest Contrast in the Subject: Working in film, without the aid of Photoshop, Capa knew from countless successes and mistakes, that the area of highest contrast needs to be in the subject. As objects receded in the distance they become less contrasty. We want our subject to have the lightest light and the darkest dark because that is what our eyes notice. Even though Capa’s compositions are not complex, he knew to look for a well lit subject.

- Finding the Unbelievable: When John Morris of Life Magazine first looked at the work of Robert Capa, he remembers not being too impressed. But thirty years later and about one thousand arguments later with Capa, he realized the strength of Capa’s work was the simple fact that Capa was there to take the picture that no one else took. We will see some incredible scenes that have more in common with the Surrealist painters than our expectations of reality. Many of the scenes Capa made during war time were too shocking to imagine. But when cities collapsed and people made life from the ruins Capa was there with a bottle of wine for their wounds and a camera for the us remember their hardships.

- Dark Landscapes: The rolling hills of Tuscany or the scenic view of a beach make for nice post card, but boring photography. In one of Capa’s funniest efforts, we will look at how the landscape of Western Europe were turned upside down during World War II. The hills which should have been used for growing grapes and watching sunsets turned dark as scores of Axis and Allied troops fought it out on the road to Berlin.

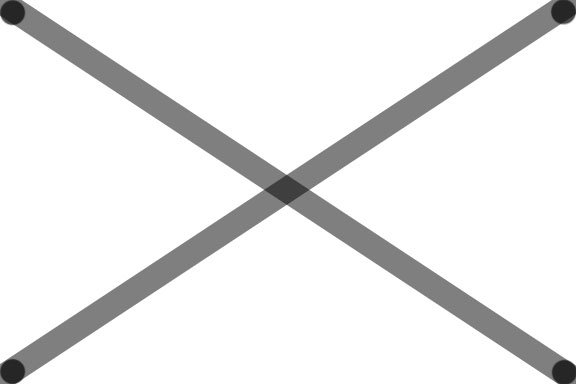

The Diagonal

When we compose a picture we have four types of lines to choose: horizontal, vertical, diagonal and curve. For the better part of his life, Capa was following battles across Europe and Asia. The feeling of action is best expressed through the diagonal. It’s an explosive force that moves our eye across the longest line in a negative. It creates a sense of movement and activity that allows the image to express the motion of a scene.

When we look in our viewfinders the tendency, especially for beginners, is to find compositions that relate vertically or horizontally. This is not because of some mysterious subconscious brain pattern. The reason is very simple. Looking through a viewfinder we immediately see two parallel vertical and two parallel horizontal lines. When a scene enters the frame that repeats either the vertical or horizontal, the shape of our negative registers mentally. We see these coinciding relationships and press the shutter.

We have been connecting dots with lines since we were children. We connect stars in the night sky and the flashing dots on a runway to form lines in our head. Instead of connecting the negative vertically and horizontally, we can connect an “X” diagonally. Once this happens, it’s like someone flipped a switch. We start to see relationships of people in space that a normal person does not need to see.

Imagine we are looking at a street scene with two men. One man is standing near an intersection, another laying on the ground and a street light in the background. Now a regular person does not need to see the diagonal line that connects the street light, the head of the man standing, and the head of the man on the ground. But as a photographer it’s good to start making these types of observations.

Does that mean photographers see “differently” that “regular” people? You bet they do. Photographers like Capa need to be able to view scenes with the imaginary diagonal lines connecting the corners of an image. This will allow the photograph to contain action. Its is the first step to understanding Dynamic Symmetry and as we will see a major tool that Capa used throughout his life.

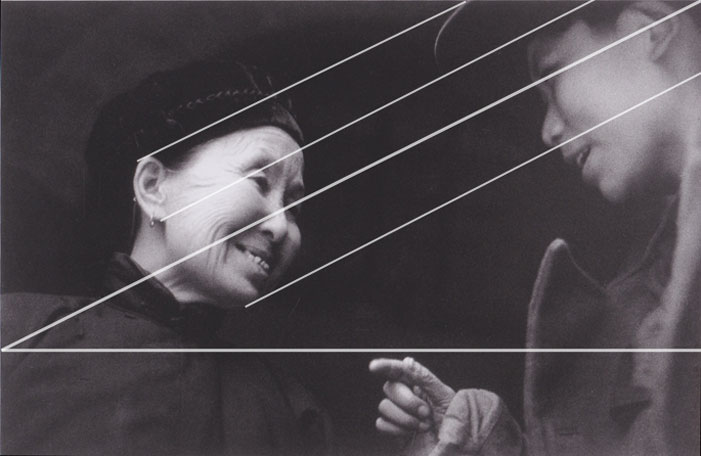

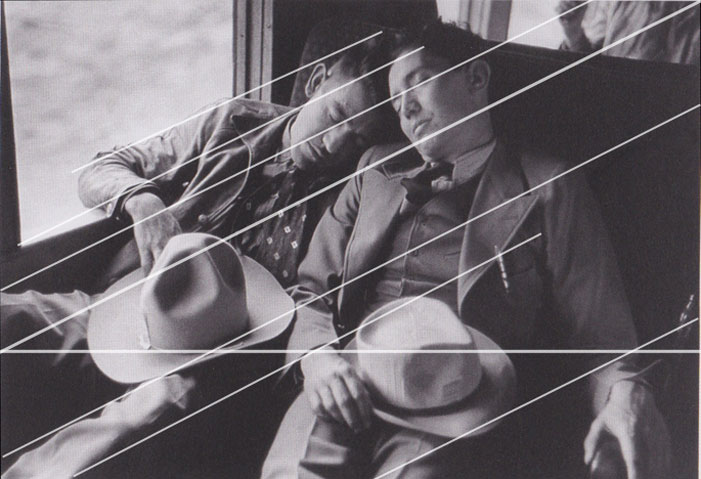

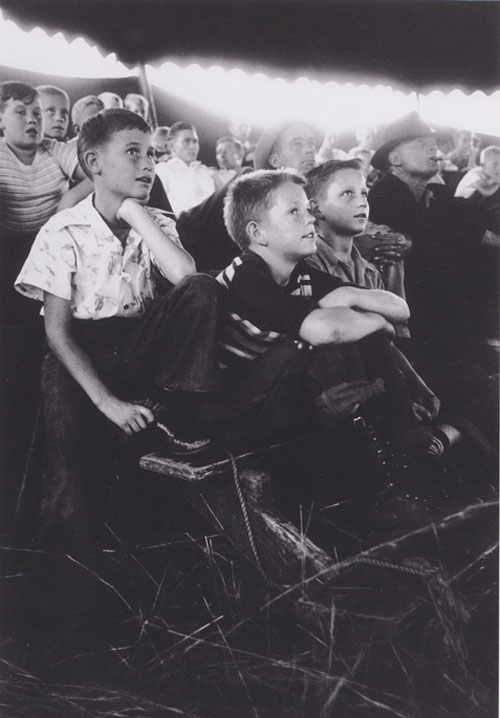

We can see in the body of images from China taken in the later 1930s that Capa uses the diagonal to connect figures in space. By composing on the diagonal he brings two people into a visual dialogue with each other. It encourages our eye to move across the entire frame of the image. We will notice that the corners of the image are dark, while there is a band of light along the diagonal. This is simple tool that we can use to quietly move the viewers eye to the most important parts of a picture.

Figure-to-Ground Relationship

How do we use the figure-to-ground relationship to our advantage on the street? Here is a simple tip that will greatly improve your images. When you look at a scene, squint. When you squint, what do you see? A good picture will be clear even if your vision is blurry. This is why photographers always say, “Study the contacts.”

If the picture is tiny as a thumbnail, it’s the same as squinting. You won’t be able to see any of the details. But as the details fade away, the light and dark relationships will scream out. If you squint while looking at any of Capa’s portraits you will see it. There is a dark figure against a light ground or a light figure against a dark ground.

If you want to test this theory further have a look at any of the posting sites. If you squint your eyes and look at a picture, what do you see? If the the figure-to-ground relationship is bad, you won’t see anything. Too many photographers rely on the distinction between sharp and soft sections of an image and completely forget to look at the figure-to-ground relationship.

The major advantage of black-and-white film is that it trains you to only see in value. Working in black and white, color is not as important because the end product only exists in a gray scale. Personally I learned photography backwards and started with color. Over the years, through many mistakes, I realized that my eyes were too preoccupied with color and sharpness and failed to register the gray scale value of a scene. Reverting to black and white for a time was very helpful because it allowed me to relearn figure-to-ground relationships and search for light backgrounds for dark subjects and vice versa.

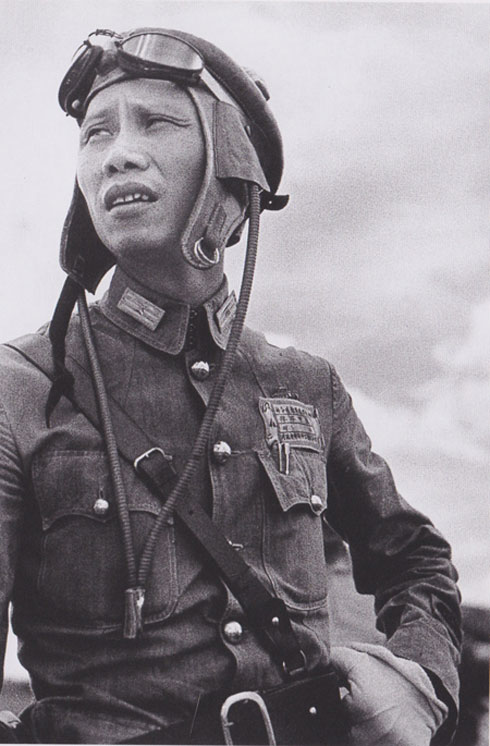

As Capa moves around a scene we often see him shoot up looking at figures. Aside from this angle making them look heroic, it also allows him to play his figures against light skies (like the Chinese pilot pictured above). It is like using a gray sky like a huge backdrop. Photographing in the real world Capa always needed to improvise. The only way for him to get certain shots was to move his feet. If we know what we are looking for, it makes taking pictures easier. Walking into a scene with a figure dressed in white, we now know immediately, we need a dark background otherwise they will get lost in a light ground. It’s a totally simple idea that gets messed up all the time.

Highest Contrast in the Subject

While I have your eyes squinted allow me to show you something else. This is a technique that is slightly adopted from Ansel Adams, passed through Myron Barnstone. For 35mm photography we can break the transition from white to black into about nine zones. Technically, we can break it down further, but for all practical purposes nine zones will work just fine. If the lightest like is 1 and black is 9, there are seven shades of gray in the middle. Stay with me here, it’s not as complicated as it sounds.

We want the our subject to be maybe zones 1 to 6, so its highlights are pure white and its shadows are a medium dark. Then we would like any other figures to be maybe a zone 2 to 7 and the background to be a zone 4 to 9. If there is an area of intense contrast outside of the main subject it’s too distracting. The easiest way to sort out the zone system while working is just squint. If you can still see your subject when you squint, you may have a picture. But if the subject disappears and you notice another, completely unimportant shape, then there is no shot.

Finding the Unbelievable

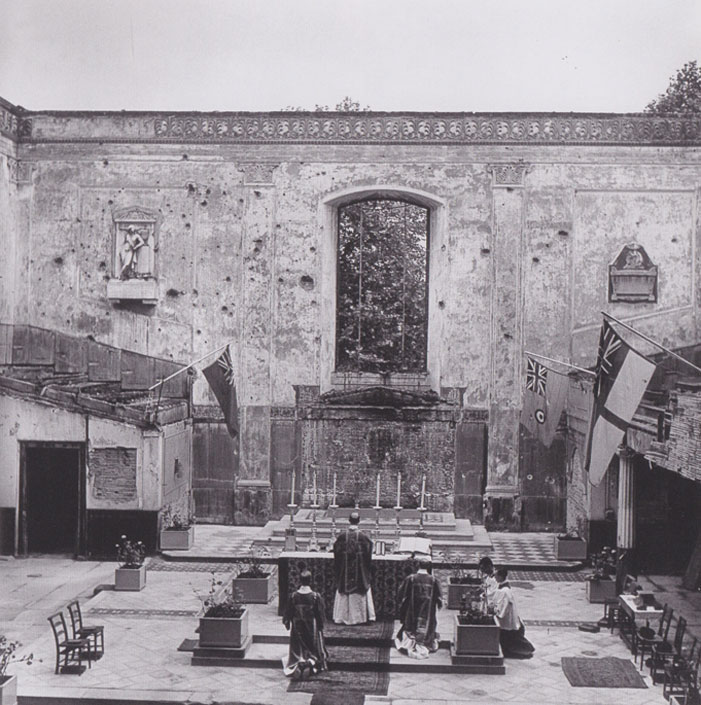

In Capa’s travels he walked through the ruins of Europe. In the rubble of Warsaw or the bombed out churches of England, he found scenes where the apocalypse had touched down. In the wake of these collapsed buildings, he found moments where people tried to return to life before the war. In the Church of Father Huchinson, Capa took the everyday scene of Catholic mass and turned it on its head. The roof of the church was destroyed by Nazi bombing raids. By shooting the scene from a distance we see the “normal looking” mass down below contrasted with the open roof of the church. At first glance it seems totally normal, in fact the lighting is quite nice for a church interior, until we realize, “Wait, where’s the roof?”

After working his way through North Africa, Capa lost his war credentials, they expired. Without credentials he was not allowed to work. He was ordered to leave the front and return to London. But staying one step ahead of the offices back in London, he managed to board a ship set to invade southern Italy.

Covering the siege of a small town called Triona, in Sicily, Capa once again found an unbelievable picture. The two soldiers sitting on the ledge relaxing. It looks ask if the entire world was collapsing beneath their feet. Capa had a knack for finding moments of calm in the chaos. It was probably a survival mechanism to cope with the war. One can only imagine what life is like after living along side the Allied troops as they advanced to Germany. During the war, the U.S. army determined that an average soldier could last 144 days in active combat before they were shell-shocked. But when they discovered that eight out of 10 infantry men were dying in the European campaign, the army decided it did not matter, since most men were not going to be alive long enough to be shell shocked. Capa was in and out of the war from the beginning of 1943 to the middle of 1945. He would work for months at a time and then head back to London. Even with the intermittent rests, it must have eventually gotten to him.

Dark Landscapes

For anyone who has lived or has traveled through Europe, you know there are some beautiful vistas. In the years between 1943 and 1945 those picturesque scenes were often scattered with tanks and infantry. The thing that stands out most about Capa’s landscape work, if we can call it that, is how a perfectly tranquil scene is shifted by the little dots of men walking along the road. Some of Capa’s photos look like they could adorn wine bottles and travel brochures seducing is into Sicilian vacations. But all is not was not well on the western front. The sprinkling of soldiers takes a beautiful landscape and reminds us, this was war. The images are a disturbing reminder of the collaborative effort required to stabilize Europe in the wake of the Nazis.

Conclusion

Capa shows incredible range in his work, a type we might all aspire towards. While he was never trained as an artist, he discovered a handful of working techniques which captivated the world. And he added one critical element to the world of photography:

If your photos are not good enough, you are not close enough.

These words ring true for all of us. The invite and challenge us to confront our subjects and fears as close as possible so that we like Ernst Hemingway will try,”… to write one true sentence.”

Wars are disturbing events that unfold for decades after the guns are laid down. We are lucky to have pioneers like Capa who put themselves along side the troops to give us a first person account. Unfortunately, it does not seem that humanity as a whole is learning from the lessons of the past.

+++ Adam Marelli is is a New York based photographer, artist and traveler, known for his workshops around the globe. For details visit www.adammarelliphoto.com.