Over the past couple of years there has been enormous interest in using manual focus lenses on the new technically advanced mirrorless cameras such as the Sony NEX–7 and Fujifilm X-Pro1. So when Fujifilm announced the new X-E1 at Photokina I was keen to see how it would handle with Leica glass.

The Fujifilm X-Pro1, introduced a year ago, is the most Leica-like of all mirrorless cameras thanks to its retro styling and the advanced hybrid viewfinder. This offers a large, bright optical viewfinder coupled with a 1.44MP LED, swappable at the flick of a switch. Unfortunately, the OVF gives no focusing information, unlike Leica’s renowned split-image mechanical focusing system, and the EVF must be selected for manual lens focusing. Buyers who think they are getting a real Leica rangefinder experience, despite the camera’s seductive appearance, will be disappointed.

A year later Fujifilm has introduced the X-E1, a smaller, cheaper camera with the same APS-C sensor but lacking the hybrid viewfiner. Instead, the internal electronic viewfinder has been upgraded to a massively capable 2.36MP OLED device that, for the first time, makes manual focusing a real pleasure. Furthermore, by dispensing with the complicated and expensive hybrid, Fujifilm has managed to slash the price dramatically. This is less than the cost of a good second-hand Leica M6 film camera.

The new Fujifilm is in many ways a superior product to last year’s complicated X-Pro1. I have been lucky enough to get my hands one of the first X-E1s to hit the British market and have been trying it with five Leica manual focus lenses. The results are astoundingly good, much better than I expected. This is perhaps the best and most accomplished non-Leica camera for Leica glass we have yet seen. It is also an outstanding mirrorless camera in its own right.

This is not a full review of the X-E1 and I make no comments on image quality, although it is excellent. I will leave that to those better qualified. Instead, it covers my experiences over the past week in just one area: Handling with Leica lenses.

Background

To all intents and purposes, the X-E1 will produce the same results as the X-Pro1; this will become apparent when the first full tests are published in a few weeks’ time. It has the same 16.3MP sensor and the same optics, so no X-Pro1 owner will feel shortchanged by “downgrading” to the cheaper version. In fact, the X-E is so right in every respect that I now see no future for the Pro. I believe the hybrid finder, good as it is, will fall by the wayside. It was a wonderful idea, but it is just too complicated and leads to constant indecision over which finder to use.

Now if the Fujifilm X-Pro1 had featured an optical split-image rangefinder, as on a Leica M, that would have been a different matter. But it didn’t, and the OVF half of the hybrid certainly wasn’t much use as a focusing tool. It is strictly a convenient, large and very bright optic for composing automatic shots.

With the X-E1 you are committed to just the one, but much superior, electronic viewfinder. The camera is all the better for it. Incidentally, the viewfinder (as on the earlier X100) incorporates a variable diopter adjustment, unlike the X-Pro1 which required a screw-in (and easily lost) fixed adjuster. This is a big improvement — although there is no indication of setting and it is simply a matter of trial and error.

Handling

The X-E1 feels chunky and solid with its high-quality all-magnesium alloy body. As a system camera, this is probably the ideal size. Make it any smaller and the lenses would seem out of proportion and the camera would look too front-heavy. The rather odd-looking Sony NEX range is evidence of this. While the X-E1 is much smaller than a traditional DSLR, it offers similar sensor size and image quality. It certainly looks much more discreet and less in-your-face; it satisfies the modern desire professional performance from the most unobtrusive little device possible.

The body is more or less exactly the same size as the fixed-lens X100 camera and has the same to-die-for retro looks. It weighs 350g compared with the X100’s 445 grams, although the X100 does have its built-in 35mm-equivalent lens. Still, even with the 18mm F2 lens mounted, the X-E1 tips the scales at a modest 466 grams, only 21 grams heavier than the X100. This is quite a feat and illustrates just how much progress has been made in squeezing maximum performance into minimum size.

It is a good looking camera by any standards. The proportions look much better than those of the X-Pro1 which has always seemed a bit wide for its height. Like the X100, the X-E1 is just right. If I care to nitpick, the omission of the optical viewfinder makes the front a very plain compared with the two earlier X series APS-C cameras.

Fujifilm has compensated by slapping on the X-E1 moniker in place of the viewfinder window. I would have preferred a graphics-free front panel, taking a leaf out of Leica’s book with the M9-P and Monochrom. These days the emphasis is on stealth. However, a small strip of black electricians’ tape over the white lettering does the trick and improves the look of the camera. With the black/silver alternative body, however, the X-E1 badge in black on the silver background is less obtrusive and probably suits better.

The controls on the X-E1 are identical to those on the X-Pro1. Everything works in the same way, including the useful Q button which gives quick access to the sixteen most frequently used adjustments. Ergonomically it is very much business as usual if you have handled an X100 or X-Pro1. My only reservation is the easily-knocked exposure compensation dial which is as loose as it was on the two earlier cameras. It is necessary to keep an eye on it to make sure it remains at neutral. Another strip of that black tape solves this problem, though.

The bright 2.8″ screen is slightly smaller than that on the earlier cameras, but that is a necessary tradeoff for the reduced overall size. Resolution is lower than on the X-Pro1 but is perfectly acceptable for my sort of use.

I collected the X-E1 with the Fujinon 35mm F1.4 autofocus lens that was overwhelmingly well received when it arrived with the X-Pro1 last year. This is an absolutely stonking prime. While I am no expert, those who do know about these things have pronounced it the equal of the Leica 35mm F1.4 Summilux. Well the Fujinon comes at a seventh of the Leica’s price. And, unlike the Summilux, you can walk into your local dealer and get one tomorrow. If all you want is an autofocus lens, or don’t already own an equivalent manual lens, then there is no question you should go for the Fujinon.

Leica Lenses

Now to Leica lenses. They are expensive, no doubt about that. But, despite the hefty price tag, a Leica lens is the nearest things you can get to an investment in the photographic world. You will not lose your shirt on a Summilux as you will with most modern autofocus lenses which contain electronics and are therefore unlikely to be around in 2060.

Leica lenses, on the other hand, are precise mechanical devices with world-class optics that stand the test of time; you could reasonably mount a 50-year-old Leica lens on a modern digital camera and still achieve superb results. To paraphrase a famous Swiss watch manufacturer’s sales pitch, you don’t own a Leica lens, you merely look after it for the next generation.

Fortunately, too, Leica M mount lenses are ubiquitous. Older lenses, still superb, are plentiful and relatively inexpensive. To attest to this, almost every digital camera manufacturer produces an adapter because they know there is a demand. If they don’t, the aftermarket will oblige.

For the X-E1 and X-Pro1 we have the Fujinon M Mount which is a precision device that, unlike some cheaper third-party mount adapters, perfectly complements your expensive Leica glass. If you choose to mount a $4,000 35mm Summilux on your X-E1, better for peace of mind to buy the official Fujifilm device.

Over the past week I have been evaluating the handling of the X-E1 with a collection of Leica lenses, from the tiny 28mm Elmarit to a quartet of Summicrons, ranging from the 35mm and 50mm through to the APO 75mm and 90mm. Leica fans know this, but it is worth explaining that all Summicrons have a maximum F2 aperture while the Elmarits are F2.8.

Summilux lenses, which I mention elsewhere, have an F1.4 maximum aperature, the same as the Fujinon 35mm. The 28mm Elmarit is the smallest current Leica lens, a real baby which looks as though it was made specially for the X-E1.

Physically mounting the lens is one thing, focus is another. This is the essence of using manual lenes and my main concern was to see how easily and quickly they are to focus.

Since all Leica M mount lenses are manual, successful use with electronic cameras demands a good system of judging correct focus. You really do need a visual clue other than simply straining your eye. Leica uses its legendary split-image mechanical system which has been the mainstay of Leica M cameras for over 60 years.

It works superbly, particularly with lenses in the 28-50mm range. However, the system does involve mechanical linkages and adjustments. With longer lenses, in particular, it is essential that the lenses and camera body are calibrated accurately. If you wish, you can send your collection back to Leica for expensive fiddling; many do.

The attraction of a camera such as the Fujifilm X-E1 (and the recently announced Leica M, due in January) is that a live electronic viewfinder can overcome these mechanical range-finding problems with longer lenses. What you see is what you get — but even so, you do need a guide to optimum focus. Fortunately the X-E1 handles this well.

The X-E1 will accommodate most Leica lenses and Fujifilm has published this list of compatible models. Strangely, three of my late-model 6-bit Summicrons (50mm, 75mm and 90mm) are not listed as approved. But they are certainly not blacklisted (as are some older lenses). I decided to ignore this list and go ahead with the Summicrons.

They work well and I have discovered absolutely no reason not to use them. There is no mechanical reason why they shouldn’t be used (as in the case old older collapsible lenses where there is often a danger of hitting the sensor when the lens is resting).

Maybe there is some obscure optical incompatibility but I certainly do not sense it. I am currently checking the situation with Fujifilm but I assume the omission it is simply a case of these Summicrons not having been tested.

The Fujifilm mount also accepts many M mount lenses made by Zeiss, Voigtländer and Ricoh. Most of these are a fraction of the price of the equivalent Leica lenses but are sometimes comparable in performance (particuarly those from Zeiss) and offer a less painful entry point if you want to go manual.

Crop Factor and Sensor Size

If you got this far you will be well of the implications of using full-frame lenses on cropped sensors such as the APS-C in the Fujifilm. Because the X-E1 (in common with the Sony NEX and most lower-end DSLRs) has the smaller sensor, the specified focal length on a full-frame lens must be multiplied by 1.5.

As a result, the Leica lenses I have been using (28, 35, 50, 75 and 90mm) become 42, 53, 75, 112 and 135mm respectively when mounted on the Fujifilm or any other APS-C camera. This crop factor is also reflected in Fujifilm’s own XF mount lens catalogue: That 35mm F1.4 is in effect a 53mm when used with the X-E1.

The so-called “full-frame” sensor, as used in the Leica Ms and higher-end professional DSLRs, is based on the frame size of 35mm film and is now the standard for sensor comparisions. There is currently a trend to more use of this bigger sensor and Sony recently announced the world’s smallest full-frame camera, the RX1.

Nikon and Canon have also just introduced full-frame sensors in new DSLRs at a lower price point that was previously the preserve of higher-end APS-C cameras. There is now no doubt that the full-frame sensor, which is much more expensive to produce, is becoming more accessible.

It would not be surprising to find a successor to the new X-E1 with a full-frame sensor within a couple of years. Then, of course, that excellent Fujinon 35mm F1.4 will be just what it says, a 35mm lens. And with Leica lenses, what you read on the barrel will be what you will get without having to multiply by the 1.5 crop factor.

Aesthetics

If you are marrying Leica lenses to the X-E1 the match must look right and be harmonious. Happily, in terms of both size and design, all Leica’s black lenses look perfect on the X-E1, even the 90mm Summicron which is actually quite small by DSLR standards. There is no sense of make-do or mend and most uninformed observers would assume lens and camera come from the same stable: one harmonious paragon, no less.

The finish of black Leica lenses perfectly complements the new camera, especially the all-black X-E1 I have been using. Note that the X-E1 also comes in a silver/black finish that looks equally good and is more traditional, not to mention more Leica-like. I haven’t tried a Leica lens on this version, but I believe the match will be just as good.

The finish on the black camera body is more subdued and matt compared with the rather shiny casing of the older X-Pro1. The X-E1 is much more handsome and better suits the Leica lenses.

The M mount adapter is unobtrusive and is styled to match the Leica glass. It works well and the new Fujifilm looks stunning with all the lenses I tried, from the miniature 28mm Elmarit through to the relatively hefty APO Summicron-M 90mm. The lenses just look right and, dare I say it, are an improvement in appearance on the rather plump and shiny black autofocus lenses in the Fujinon XF range, especially when fitted with their dustbin-sized hoods.

With a Leica lens attached, the camera looks wonderful, a marriage made in heaven. If Leica had had a cooperation with Fujifilm instead of Panasonic, this is exactly what the M Mini would have looked like.

Setting Up the Camera

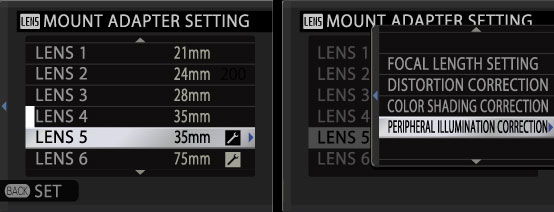

The Fujifilm M Mount Adapter creates a 27.8mm distance from lens mount to camera mount in order to compensate for the difference in sensor placement compared with, say, an M9. The adapter includes connections which, Fujifilm claims, pass information to the body based on preregistered lens profiles. To ensure optimum results, though, it is still necessary to select manually the focal length from a menu screen.

There are presets for 21mm, 24mm, 28mm and 35mm lenses plus two further adjustable custom settings to cope with a other focal lengths such as 50mm, 75mm, 90mm and 135mm. You thus have six lenses in memory at any one time. For any selected focal length there are finer adjustments including distortion, color shading and peripheral illumination correction. I have used only the standard settings and I have also been unable to try the XE with wider-angle 21 and 24mm Leica lenses.

A button on the side of the adaptor gives instant access to the lens selection menu so you can make quick adjustments on the fly. If you are using the viewfinder, this dialogue box appears in front of your eye so you can adjust the lens setting without needing to look at the rear screen.

The final thing you need do is set the focus mode to M (manual) using the focus mode switch on the front of the camera, next to the lens mount. And don’t forget to set it back when you remount your Fujifilm lenses. I have been caught napping by this on a couple of occasions and was left wondering why autofocus wasn’t working.

Manual Lens Fetish

Why bother fiddling with manual focus when the excellent Fujifilm autofocus lenses do the job for you? Ask any rangefinder enthusiast and he will tell you there is a sense of satisfaction and involvement in manual focus photography that is quite lacking with autofocus. There is a quietness and precision that contrasts with the whir of the focus motor, however subdued. You definitely feel more involved and more in control, particularly when homing in on the subject.

If you are really to enjoy manual focus, however, you do need a lens built for it. Autufocus lenses are seldom exciting when in manual mode. Manually focusing the Fujinon 35mm XF lens (or any other of the X mount Fujinons) was a deeply dispiriting experience when I tried it with the X-Pro1 last year.

The focus ring required more than two turns from near to infinity and I was forever twiddling it. This is especially so if you forget which way you need to turn it; you are left drowing in a sea of bokeh without a clue to direction. Meanwhile, you’ve lost the shot.

Since then, camera and lens firmware updates have dramatically improved manual focus with the Fujinons. A further refinement of the new firmware is that when using the automatic lenses, the aperture is opened wide automatically to further improve focus accuracy. This cannot happen with Leica lenses, of course, because the camera has no control over aperture. In low light conditions, focus accuracy can be improved by widening the aperture manually and then stopping down once focus is locked.

Sure, the Fujinon lenses can be manually focused if you really must, but only when you really must. Otherwise it’s best to just let them get on with their autofocus wizardry (which now works faster, incidentally, since the firmware upgrades). In contrast, the Leica Elmarit 28mm has a focus ring that goes from 70cm to infinity in under 180 degrees.

It feels just as quick and precise as it does on a Leica and it makes manual focus an absolute pleasure. Manually focusing any of the Fujifilmnon lenses after the Elmarit is like wielding the steering wheel of a 1970s Cadillac instead of a modern sports car.

Putting Things in Focus

This is the crux of the matter: how to tell when you are in focus? With a Leica M camera you simply align the split image in the viewfinder and trust to luck that the system is accurately adjusted. It works well most of the time and is unlikely to give problems, especially with 50mm and wider lenses. It is possible to achieve accurate focus very quickly and some Leica fans reckon they can beat an autofocus lens any time. In many ways it is still the ideal way of setting focus manually, despite all the technical advances we have seen in the past twenty years.

After the week with the X-E1 and the Leica lenses I returned to the M9 to do some comparison shots and immediately felt back at home with the split-image rangefinder. If I am honest, it is a tad quicker to find focus than with Fujifilm’s EVF. The Fujifilm, though, is satisfying and accurate; it just goes about things in a different way.

The challenge with a non-rangefinder camera is to provide some visual clue that the subject is in focus. Sony have so-called Focus Peaking where the outline of the subject changes color to indicate the subject in focus. I have tried this on a friend’s NEX-7 and find the red outline a bit distracting, although it does work well. Fujifilm have not adopted such dramatic visual clues, but there is nevertheless a clear indication of when accurate focus has been achieved.

Focus is actually very accurate and extremely quick. The superb 2.4MP OLED viewfinder helps of course. It is so good that you can more or less judge things without any assistance when using longer lenses. It gets even easier if you prod the rear command dial to bring up three-times magnification; and easier still if you click the command dial to the right to get a ten-times magnificatied image. It is then possible to fine-tune the focus with absolute confidence.

As I said, Fujifilm does not claim to have focus peaking as found on the Sony NEX. But the viewfinder does give a clear visual indication of focus once you learn to recognize it. When focus is achieved there is a sort of shimmer or mild moiré effect that tells you all is well. I’ve seen this described as a “popping” but I think shimmer is more accurate.

Strangely, this phenomenon is much more pronounced when using the longer Leica lenses, in particular the 75mm and 90mm APO Summicrons. Most times, with these longer lenses, you do not even need to use the focus magnification button. It is also quite distinct when the 50mm Summicron is mounted.

Frankly, I am not sure whether this shimmer is by design or is a coincidental optical phenomenon, but it is quite distinct and impressive.

Wider lenses, on the other hand, offer slightly less visual clue to focus and you really do need the 3x or, better still, the 10x magnification. The focus shimmer is harder to detect with the 28mm Elmarit and only a little better with the 35mm Summicron. It is still there, but the shift from focus to out-of-focus is much more gradual. With these wider lenses you definitely do need to prod the focus magnification button if you are not to be misled.

Initially I had more out-of-focus shots with the baby Elmarit than with any of the others. This was down to my inexperience, I have to say, and by the end of the week, aided by the 10x magnification, I was managing sharp results and feeling confident.

Bear in mind, too, that the 28mm Elmarit and 35mm Summicron are great lenses for zone focus, where you set a range, using the markings on the barrel of every Leica M lens, to take advantage of the wide depth of field. With the 28mm Elmarit set to F16, for instance, everything from 0.8m to infinity will be in focus. Even at F5.6 you can be in focus from 3m to infinity.

So, provided you avoid close-up shots and choose a smaller aperture, most street photography opportunities are covered without the need to fiddle with the focus. This is one reason why the 28mm and 35mm focal lengths are so popular for street photography.

By contrast, longer lenses require more critical attention to focus and it is encouraging that the X-E1 works so well with the 50mm, 75mm and 90mm lenses I tried. On the Fujifilm they equate to 75mm, 112mm and 135mm. Incidentally, they all make excellent portrait lenses.

Both the wider lenses, the 35mm Summicron and the 28mm Elmarit have a stubby finger rest or lever on their focus rings. This is added because grabbing the focus ring on such a compact lens can be awkward; so the lever enables focus using one finger. It is very precise and ergonomically perfect.

This lever has two other benefits. First, when positioned at 4 or 5 o’clock (looking from the back of the camera) it tells you the lens is in an optimum zone focus state. For quick shots you can use this guide to focus without checking. You can, in effect, focus by feel. Finally, the lever when placed at 6 o’clock acts as a stand for the lens and keeps the camera upright when on a flat surface. Otherwise the camera flops down on the lens. This benefit is mere happenstance, but nonetheless welcome.

After the week there is now no doubt in my mind that focus on the X-E1 is very precise, particularly in 10x magnification mode, and very enjoyable. It is almost as much fun as using a Leica. With the longer 75mm and 90mm lenses I much prefer the Fujifilm’s EVF focusing to using the split image on the M9. The 90mm and the longer 135mm lenses have always been a challenge to the Leica split-image system and require a degree of care, not to mention accurate calibration of lens and camera.

Camera Shake

None of the Leica lenses has image stabilisation mechanics but nor do the Fujinon primes, including the 60mm (90mm). Camera shake is therefore a danger when using longer focal lengths. It is wise to keep an eye on the automatic shutter speed setting shown in the viewfinder; alternatively manually select a speed that will reduce the risk of camera shake. Fortunately, all the longer lenses I used are bright F2s and that helps by permitting faster shutter speeds.

Exposure

It is worth mentioning exposure here, although it is not material to this focus-related discussion. With Leica lenses mounted on the X-E1, you have the same exposure options as you do with an M9. You can choose aperture priority by setting the speed dial to A and juggling with the aperture; or shutter priority by dialling in a specific speed and then adjusting the aperture to achieve the correct exposure.

When using time priority an exposure scale appears in the viewfinder so you can manually change the aperture to achieve an acceptable exposure. The scale also appears if you move away from automatic speed and wish to set both speed and aperture to specific values. The only thing you lose in relation to the native automatic Fujinon lenses is full auto mode. With both aperture and the speed set to A for automatic, the Fujifilm lenses operate completely automatically, selecting aperture and speed according to the circumstances.

With Leica and other manual focus lenses the camera has no knowledge of the aperture setting other than the amount of light entering through the lens. There is physically no possibility of the camera controlling the aperture, only your fingers can do that. Also, as with Leica Ms, there is no record of aperture setting in a photograph’s metadata.

All you get is speed and lens focal length; you have to remember what aperture you were using at the time. This can be annoying for those used to fully automatic cameras where aperture is recorded as a matter of course.

What you do get with this viewfinder, though, is an incredible amount of detail. It is possible to get a precise feel for the exposure of the resulting image simply by looking at the scene in the finder.

The New Leica M

At the back of my mind throughout the week with the Fujifilm was the newly announced Leica M with its new 24MP full-frame CMOS sensor. There are no reviews yet, although the few people who have handled the new M are saying that it should provide even better results than the M9. The CMOS sensor enables live view for scene composition in the much improved rear screen. Let’s not mention the screen on the current M9 and M-E: it is about as exciting as watching a 1950s television and is a travesty on a $5,000 camera. In my experience it is useful only for consulting the menu.

The M also allows the mounting of an LED viewfinder in the hot shoe to provide live focusing in exactly the same way as on the Fujifilms. It will incorporate focus peaking, which might give it an edge and perhaps compensate for the relatively lower resolution of the M’s electronic finder. This Barnacle-like addition to the M’s hot shoe is the rather long-in-tooth Olympus device (rebadged as the Leica Visoflex EVF2) with a mere 1.4MP under the hood.

This is the same unit I used on an Olympus PEN three years ago. Inevitably this viewfinder will compare poorly with the OLED device in the X-E1. On the positive side, the EVF2 has a 90° swivel so you will be able to use it effectively for low shots.

Verdict

In many ways, the Fujifilm X-E1 is a mini M. It possesses a much better built-in rangefinder than the rather elderly unit that will sit in the hot shoe of Leica’s finest when it arrives next year. It does lack Leica’s wonderful mechanical split-image viewfinder and has to make do (for now) with a smaller sensor offering fewer pixels. I suppose you do have to sacrifice something in return for the substantial difference in price.

That said, there is undeniably something very special about a Leica M. Nothing else compares with having one in your hand and appreciating the feel, solidity and precision of the finest engineering in the camera world. Yet with the Fujifilm X-E1 you have a massive dose of M magic at a fraction of the price.

The X-E1 is the best mirrorless camera for Leica lenses that I have yet tried. The focus system, aided by the excellent viewfinder and the useful focus-point magnification, is as good as you can get. If you own a stack of Leica lenses, go out and spend $1,000 on this high quality little body and you will have tremendous fun.

If you already own Fujifilm lenses in the range 18-60mm, then there is little if anything to be gained from using Leica lenses other than the satisfaction of manual focus involvement. If, on the other hand, you are lucky enough to possess either of the longer APO Summicrons, the 75mm or 90mm, you will have a blast when you click one into the M-Mount on your Fujifilm.

Alternatives

The Sony NEX-7 (or the new NEX-6) is possibly the equal of the Fujifilm X-E1 in terms of IQ; it certainly has more pixels to play with. It also has the same 1.5 crop factor. I simply prefer the appearance and the control layout of the Fujifilm.

As far as sensor size is concerned, my tip is to go no smaller than APS-C if you want to avoid your lenses becoming too long. Smaller sensors result in a bigger crop factor which further increases the focal length. For instance, the otherwise excellent Olympus OM-D has a Micro Four Thirds sensor with a crop factor of 2. This means that the Leica lenses are effectively doubled in focal length. Even the little 28mm Elmarit turns into a 56mm and the 90mm Summicron becomes a monstrous 180mm. The Nikon 1, with its 2.7 crop is even less appropriate for use with standard full-frame lenses.

Republished with the friendly permission of Michael Evans who is more of a computer-centric guy, as one can easily tell from his website Macfilos.

Michael formerly worked as a technical journalist and owned and ran a public relations consultancy in London.

Retired, Michael enjoys all sorts of quality gadgetry, including photography.

Below: Two similar river views from the 35mm Summicron. They were taken on different days so lighting conditions are not the same. The one on the top is from the Leica M9, that on the bottom from the Fujifilm X-E1. Both are from the camera without enhancement.

+++ Order the Fujifilm X-E1 from Amazon (black/silver), B&H (black/silver) or Adorama (black/silver). We recommend you use the best available glass, so go for the 35mm F1.4. For the latest X-E1 reviews and hands-on reports, don’t miss our dedicated, continuously updated The Fujifilm X-E1 File.