Street photography and shyness, they don’t match, do they. Street photography requires an outgoing personality, eager to not mind what passersby think, not shying away from even confronting people. People can get upset if not aggressive when they see a stranger’s camera pointed at them. Some photographers just don’t care. Others are careful enough to not get caught while snapping. Both approaches are questionable. We’re no Peeping Tom. We should earn respect and treat people the way we like to be treated ourselves. I sure don’t like someone throwing the camera into my face. What about a photographer’s “humanist” approach, such as of a photographer who initially preferred to shoot objects because he was too shy to shoot people. Of course, we’re talking of Robert Doisneau.

Doisneau was a French photographer who roamed the streets of Paris in the 1930s with his Leica. His humanist photography was all about respect. Not about glorifying and beautifying an undoubtedly often beautiful world. But rather about concentrating on the underclasses or those disadvantaged by conflict, economic hardship or prejudice.

Humanist photography “affirms the idea of a universal underlying human nature,” someone once wrote, as a “lyrical trend, warm, fervent, and responsive to the sufferings of humanity.”

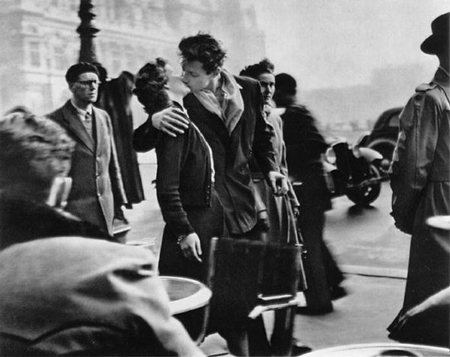

Doisneau’s most iconic photograph of course is Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville. A love couple’s standstill of time amidst urban bustle.

Doisneau, writes the Economist, is often grouped with 20th-century humanists behind the camera, like Brassaï and Edouard Boubat, who documented everyday European life as people struggled to recover their lives after the Second World War.

It wasn’t photojournalism, but it represented freedom to photographers. Doisneau felt that daily life was the most exciting of all:

No movie director can arrange the unexpected that you find in the street.

Doisneau, the street photographer who kept his distance. Writes the Economist, and because it’s so beautiful I quote in full:

Doisneau was a slow, deliberate photographer, not a hunter. He preferred to capture impersonal cityscapes from high vantage points, and the streets of Paris when drenched in rain, fog or snow. As a result, some of his photos lack an emotional punch. By shooting groups of people from afar, perhaps he sought to show togetherness after so much conflict. He was bored by the countryside, preferring the business of city, and seemed to crave the idea of friends coming together in dark times. But distance between photographer and subject translates to distance between viewer and subject.

While Doisneau is sometimes compared to Henri Cartier-Bresson, the latter was the archetypal 20th-century street photographer and photojournalist, never shying away from the gritty or the troubling, even as he made beautiful images. Doisneau, unlike the upper-crust Cartier-Bresson, was from a middle-class suburb, documenting “the ordinary gestures of ordinary people in ordinary situations”, while making sure never to strip them of their dignity. He got close, but not too close. His pictures do not always elicit strong emotion, or much pain. While many are melancholic, few are heart-wrenching.

Maybe Doisneau never overcame his fear of getting close to people, at least from behind the lens.

In an interview from 1982, he said the camera gave him courage when he was afraid of going into unfamiliar places, such as nightclubs:

I was not afraid, because I had my camera with me, just like the helmet for a fireman.

But once he shot what he considered to be a good photo, he knew it: he would get shivers down his back, and then run away.

What about you?

Rather the shy type?