The photo of a naked girl fleeing from a napalm cloud is one of the classic symbols of the Vietnam War. A historian analyses the image-related connotations and criticizes the media. Should a photographer — or any journalist for that — help victims of atrocities while trying to perform his or her duty of reporting? Not an easy question. By helping, an image that might become iconic to document atrocities may get “lost.” And ever wondered how removed from reality unedited images can be? Such is the case with the “napalm girl.”

War is always brutal — for soldiers and civilians alike. Innocent bystanders are always victims of war, in modern day conflicts there are often more “collateral victims” than uniformed dead. In Third World struggles in former colonies, the indigenous population was always particularly hard hit. This holds true for the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1975 in which something like three times more civilians died than soldiers on both sides.

Coincidentally, at a time when U.S. President Barack Obama has called on two very different Vietnam veterans, John Kerry and Chuck Hagel, to join his new cabinet, a startling documentary has been released which maintains that the scope of war crimes against the Vietnamese people was much greater than had been previously acknowledged. It is, however, the iconic images rather than books on the subject that continue to have more impact on public consciousness around the world.

The atrocities of South Vietnamese and American forces have been officially recognized while the crimes of the communist North Vietnamese are seldom mentioned. Even more interesting than this imbalance is the fact that the two most important visual icons in the collective memory of the Vietnam War should be viewed in a much more differentiated manner.

An Execution on Camera

The execution of a Viet Cong fighter by the South Vietnamese Police Chief of Saigon on February 1, 1968, during the Tet Offensive of the Communist guerrillas, is recognized as the embodiment of inhumanity. But there are grounds for doubt, as the young man shot in the head had allegedly cruelly slaughtered civilians earlier on — a fact that can not be shown in the famous photograph.

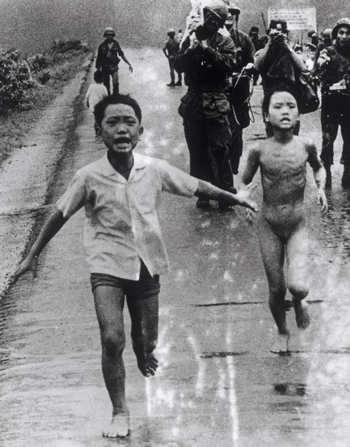

The situation in the second iconic image is completely different. It was taken on June 8, 1972, and shows a naked, screaming girl, arms spread out helplessly, on the road to Trang Bang. She was nine year old Kim Phúc and was without a doubt an innocent victim: liquid fuel from a bomb sheath had burned large parts of her back.

The Vietnamese photographer, Nick Út, took the famous shot that was awarded “World Press Photo” in 1972 and a year later won the Pulitzer Prize. His picture, now known as the “Napalm Girl,” has been published in numerous magazines and books and screened in hundreds of TV documentaries. It has been used in propaganda posters and artworks, other photographers have recreated or distorted the original.

“Visual History” Expert

The whole history of this world famous photo is now explained by Gerhard Paul, history professor at the University of Flensburg and a leading expert on “Visual History.” In his new book BilderMACHT (power of images) he has put together 17 detailed studies of various famous photo images that have influenced our collective consciousness. These include photos of Adolf Eichmann before court in Jerusalem 1961 in a glass box, as well as an aestheticized portrait of Mao Tse-tung and TV images of the attack on New York’s World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

The picture was taken in the village of Trang Bang, north west of Saigon, about a mile away from the front line. In early June 1972, the United States had started to “vietnamize” the war in Vietnam, i.e. to withdraw their own forces and hand over operations to South Vietnamese combat troops. There were therefore no U.S. soldiers fighting there, just the 25 Vietnamese divisions. The Americans on the famous image were mainly war correspondents and photographers who had driven down that morning anticipating impressive combat action — among them Nick Út.

It Was Even Friendly Fire!

Around noon the local South Vietnamese commander asked for an air strike in support of the soldiers in ground combat. At least five incendiary bombs hit their own positions around Trang Bang. The few houses were also targeted although there were no indications of resistance.

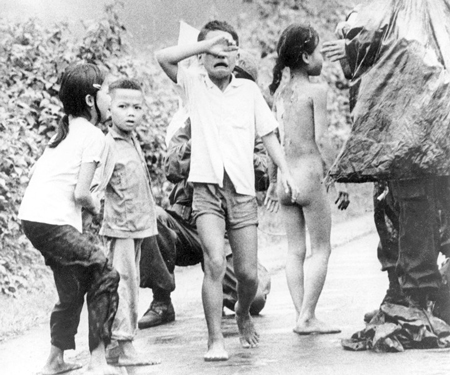

Numerous South Vietnamese soldiers were also injured by “friendly fire” in this misguided attack. Peter Arnett, the war reporter (then Associated Press, later CNN) and Fox Butterfield (“New York Times”) later recalled that, apart from the correspondents, there were no foreigners at the area.

What happened next was just as shocking — and reflects negatively on correspondents on the spot: they continued doing their jobs photographing, filming and gathering impressions for newpaper articles as if nothing happened. Nick Út also initially took numerous shots with his Leica; only after that he and his colleagues took care of the injured children. This was never mentioned in retrospect.

Correspondents and War

Gerhard Paul states, “Contrary to what Nick Út later maintained, these particular shots do not mirror the war itself, but rather the behavior of the media towards war victims.” The historian carefully reconstructs how the famous picture was modified, it was in fact cropped — and why subsequent images were sorted out.

Neither the image shot slightly later by Vietnamese photographer Hoang Van Danh of Kim Phúc no longer screaming in pain became famous nor a picture showing the correspondents at work. Both images would probably have reduced the impact of “Napalm Girl.”

The original shot was also enhanced by significant trimming: the napalm smoke clouds on the horizon appear threatening, similarly the men with helmets in the background — not soldiers, but correspondents. But above all, the picture margin on the right showing TIME Magazine reporter, David Burnett, calmly changing the film in his movie camera while Kim Phúc ran screaming past him, was cropped.

Career of an Icon

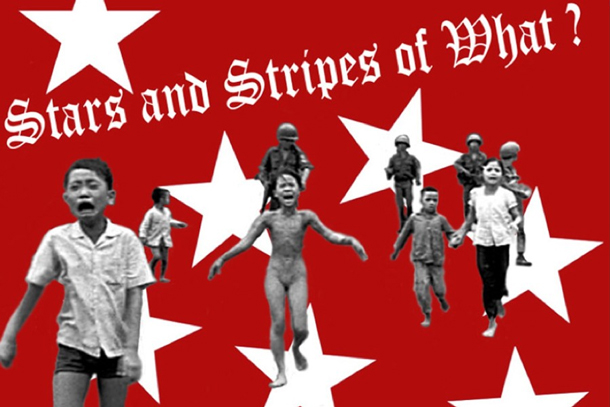

The very next day newspapers in the U.S. and around the world printed the trimmed and slightly retouched version of Út’s photo. Thus began the career of this image, which became a campaign poster in the impending election for the U.S. presidency — and soon after the subject of somewhat tasteless artistic adaptations.

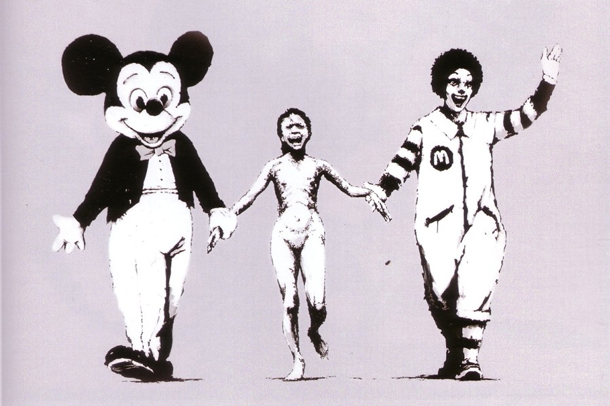

Gerhard Paul evaluates street art artist Bansky’s version of “Can’t Beat the Feeling”, in which the screaming girl is mounted between Mickey Mouse and McDonald’s advertising mascot: “Kim Phúc, a global symbol, is placed coequally between two central advertising icons of the century. She is thus ostensibly degraded to the status of an advertising cliché.”

The meticulous analyses in Paul’s new book illustrate why we should handle image icons circumspectly. He also demonstrates how far removed from reality unedited images can be, this applies even more so to retouched and edited images. In today’s image-overloaded world, the precision and accuracy of his research affect us beneficially.