By IHTISHAM KABIR

When photography was invented in 1840, literature warmly greeted it. Why? I think the ability of photographs to precisely describe what is in front of the camera caught the imagination of writers who felt less threatened by photography than painters did. Authors as diverse as Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, John Ruskin and Virginia Woolf were early supporters of photography. Some writers quickly recognized photography’s marketing potential: Whitman and Mark Twain used their photographic portraits for public relations.

Novelist Honoré de Balzac was frightened by photography. He believed that all living bodies were made up of invisible layers of skin, and taking a photograph peeled away a layer. Thus, he thought, repeated exposures to a camera can eventually peel away all the layers that make up a person and kill them. But Balzac did pose for photographic portraits. Presumably his ample girth — equivalent to numerous layers — reassured him.

In fiction I have read, the most memorable observations about photography were in Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” where the colorful character Melquiades sets up a primitive photo lab in the remote South American town of Macondo.

The enchantment that the novel’s protagonist José Buendia feels about photography turns into obsession as he tries to photograph god in order to prove his existence.

In recent times, the authors Eudora Welty, Allen Ginsberg, Michael Ondaatje and Bruce Chatwin have pursued photography seriously. Among photographers, Robert Adams and Wright Morris are established writers.

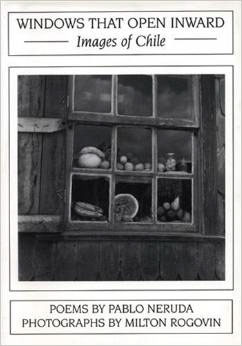

Writers and photographers often collaborate on projects, but memorable results are sparse. Poet Pablo Neruda and photographer Milton Rogovin made a haunting book of poems and photographs called Windows that Open Inwards.

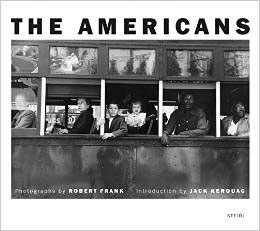

The author Jack Kerouac in the preface to The Americans, a book of photographs by Robert Frank, famously said that “Frank sucked a sad poem right out of the heart of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

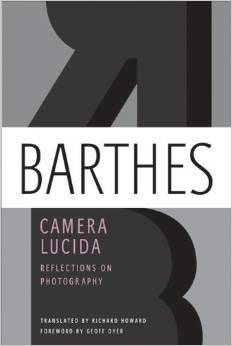

Philosophers such as Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, John Berger and Susan Sontag have written intellectual discourses on photography. I find Barthes’ Camera Lucida particularly engaging. Discussing a portrait of Napoleon’s younger brother Jérôme, Barthes expresses his absolute amazement that “I am looking at eyes that once looked at the emperor.”

He admits that others might not find this fascinating. “Life consists of these little touches of solitude,” Barthes concedes.

For more on Ihtisham Kabir visit his Facebook page Tangents.