Digital photography has come a long way since the 90s, the early days of consumer digital photography that were filled with cameras that broke new ground, though not necessarily in directions that were widely adopted. After more than a century of “conventional” film photography, also the old mechanical ways became questioned: be it the sensor, processor, pentaprism or viewfinder, we’re steadily entering new territory by moving away from old industry standards that prevailed for so long. One mighty heritage of the past remains largely untouched so far: the largely still mechanical shutter. The future that will really break new ground is a non-mechanical global shutter.

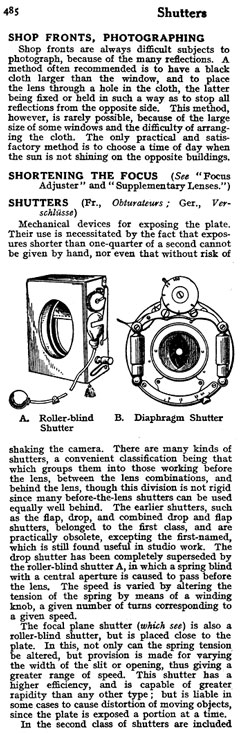

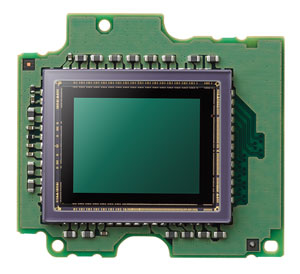

From the different mechanical shutters — simple leaf, focal-plane, diaphragm and central shutters — digital imaging sensors moved to electronic rolling and global shutters. A rolling shutter that’s commonly used by CMOS sensors scans the image in a line-by-line, kind of cascading fashion so that different lines are exposed at different instants, as in a mechanical focal-plane shutter. But rolling shutters can cause effects such as wobble (jello effect), skew, smear and partial exposure.

Among other benefits a global shutter allows to take instant pictures with no lag — as there is no mechanical shutter — and with no “click clack” noise. The shutter is absolutely silent.

Another big advantage of a totally electronic global shutter is faster flash sync speed and the removal of a mechanical system which costs money to manufacture and can wear out.

But more importantly, by representing a single point of time, global shutter exposures do not suffer from a rolling shutter’s motion artifacts. With a global shutter sensor, the scene is “frozen” in time producing minimally distorted images. Avoiding these rolling shutter effects is especially crucial in video.

First off, not all rolling shutters are alike and the ideal global shutter doesn’t exist, just as the ideal rotary disc shutter never existed. However, electronic global shutters have the potential for the greatest accuracy and uniformity across the frame.

It would be baloney to proclaim every camera must have a global shutter. That would be like saying all cameras must be black. Stay away from anyone who proclaims a technology is good or bad by itself. The simplest thing to do is forget about technology and use the camera for what’s it’s supposed to be used for: photographing. A painter won’t start creating a masterpiece with an untested brush recommended by an expert, so why would a photographer do the same?

But modern cameras are very complicated. Soon we will reach a point where technology is so beyond us that we can’t tell any difference between rolling, global or whatever shutter. For instance, a rolling shutter can be better and more “filmic” than global shutter. That’s especially welcome in dim light where rolling shutters tend to perform better. Also, the rolling shutter blur can imply the impression of movement.

Recent advances in CMOS technology has greatly reduced the extent of the rolling shutter effect on higher-end sensors, but it is none the less still present and is not possible to eliminate entirely. True, a CMOS sensor by design has to be read in series and thus creates a rolling effect as values are sampled while CCDs on the other hand dump all their information in to a buffer at the same time and the buffer is then read, thus the sampling occurs at the same moment.

Global shutter, however, is difficult in CMOS. Especially the penalty in sensitivity seems to be large. But CCDs aren’t used anymore because today they don’t offer significant advantages for stills photography. They still do for video.

Fact is, modern DSLR cameras still come with mechanical rolling shutter while slimmed down mirrorless cameras provide that awesome fake shutter sound… Actually the Nikon 1 J series is the only interchangeable lens system camera without any physical shutter. It’s not a true global shutter, however, just a scanning shutter that can work fast enough to fake it.

But seriously, why would it matter to any photographer whether it’s rolling or global shutter, because the human eye can hardly tell any difference. True, at high shutter speeds the second curtain may start hiding the sensor before the first curtain finished its move. When this happens, an actual slit is traveling across the sensor. But how often did this happen to you while shooting?

Anyone can work around any rolling shutter “deficiencies” in most situations. Still, global pure non-mechanical shutter is the future. Because, again, it would allow to take instant pictures with no lag — as there is no mechanical shutter — and with no “click clack” noise. Total silence.

Another big advantage of a totally electronic shutter is the way faster flash sync speed — because when the flash pops the whole sensor is getting hit with the light from the flash — and the camera gets rid of a mechanical system which costs money to manufacture and can wear out.

For the moment rolling shutters are here to stay. Most likely we’ll first get a hybrid shutter system where the first curtain movement can be done by CMOS censor for faster response time. Although the difference is measured in milliseconds, it’s still a small improvement. If I’m correct Sony has this in it’s latest high-end DSLRs. This solution comes very handy with the electronic viewfinder and see-through, non-moving SLT mirror.

In the case of the Sony A99 rolling shutter artifacts in video are pretty minimal. If you pan at anything approaching a reasonable rate while filming, you’re not likely to notice them at all.

For the moment the mechanical shutter, a thing of the past, is here to stay. But the camera of the future will apply a fully electronic global shutter that opens up pretty darn good new possibilities in photography.