You might never have heard of Kenro Izu. Well that’s a shame because the Japanese-born naturalized American citizen who has lived in New York City for the past 40 years is known worldwide as one of the most celebrated photographers specializing in still life, a classical yet rarely-practized photography genre nowadays. Izu takes the genre to amazing heights — thanks to a custom-made camera built to produce 14×20 inch negatives to make 14×20 inch prints.

His camera, custom-made for him in Chicago 30 years ago, weights 150kg with lens, tripod, file cartridges and other parts to travel. The negatives are so thick and heavy that Izu can only bring about 80 of them on a trip.

And the printing paper is not commercially available, so he needs to hand make printing paper by brushing a sensitizer of platinum and palladium mixture over a specially treated watercolor drawing paper.

That’s a little bit different from photographers with small cameras who wish to make large platinum prints for their beautiful quality. They can obtain enlarged negatives — or digitally generated large negatives.

To Izu, he believes genuine platinum prints without any process in-between the original negative and print is the purest form to portray life. He has followed this process for the past 30 years.

For him, photography is much more than just taking a picture. Once he starts a project he has to continue to observe the stages of life. He must be able to sense the moment when he communicates with the subject. Right, communicates with the subject.

His photography doesn’t come easy. Sometimes he sits for hours without taking a picture and his team asks, “Mr. Izu, what’s the difference from two hours ago and now?”

He would reply, “I Just didn’t sense it.”

Photography for Izu is a very personal experience. The slightest movement of air or wind that creates a certain atmosphere can be all-important. People might think he’s meditating because he sits by the camera for an hour without moving. But he is just watching and trying to sense the right moment.

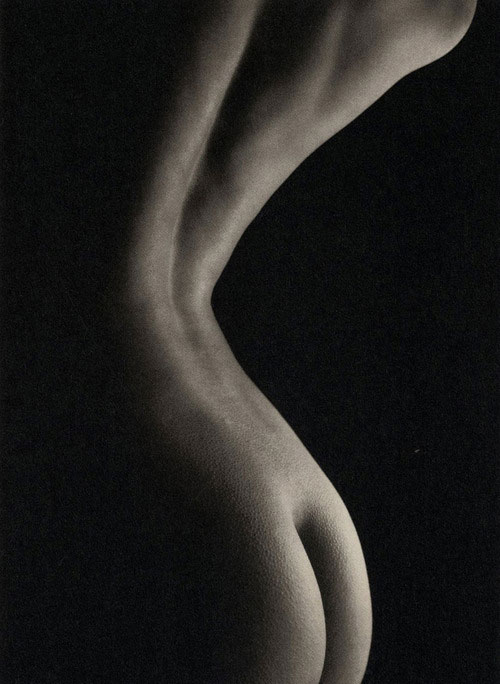

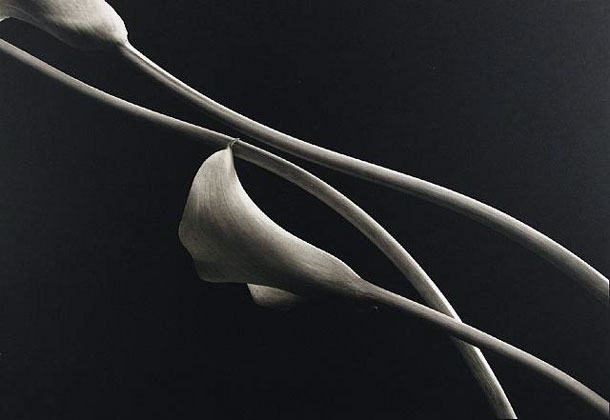

Izu adores any life form and finds beauty in every moment, every stage of life. A flower is beautiful when in full blossom, but he can admire the beauty of the same flower when its bloom is over and wilted — or even when it is dried. And the same can be said of a human body or ancient, sacred places of worship that are also part of his series of photographs.

So Kenro Izu’s photography focuses not only on the beauty of life, he first and foremost has a deeply philosophical, humanitarian side.

A bit tricky are the technical aspects of his gigantic camera. The depth of field is very narrow, maybe within few centimeters. Particularly in the body study, live bodies cannot stand still perfectly. They often move out of focus or even out of the frame of the picture.

Flowers, on the other hand, stay still, but the dimensionality of the flower itself is somewhat challenging to get in focus entirely.

So here is a thinking photographer who started with washing dishes in a Japanese restaurant in New York and made it to become a, yes, humanitarian. Izu has founded Friends Without a Border, a non-profit organization dedicated to raising funds for children’s hospitals in Cambodia.

Izu puts own artwork up for auction and mobilizes his assets to help treat children — hundreds of thousands already — under the age of 15 who pay only a pittance and only if they can afford it.

See? Photographers still can change the world.

It all started when he saw a girl in Cambodia dying in a bed. For the first time in his life he could not pretend he didn’t see or ignore the pain in his heart.

His humanitarian work is mostly financed by his photo auctions in New York, now in its 15th year this December.

How he started as a photographer?

He took thousands of pictures. He was a totally naïve photographer. He took everything because I didn’t know what he was looking for.

Somehow, he still doesn’t know today.

Says 63-year-old Izu, “I’m still looking for myself. It’s kind of embarrassing. At this age, I should know myself.”