Current sales figures for serious cameras are troubling, to say the least. They nosedive. While we photography enthusiasts are a niche who cares about nice ISO values, good glass, proper processing speeds, form factor and accurate image rendition, most people don’t. Significant inventories of the established camera brands remain unsold, not least because a bloated product lineup confuses most consumers and offers only incrementally better results than fancy convergence devices. Real innovation is offered by smartphones that currently call the shots in imaging technology: they reinvent photography, the established camera world is ready for full disruption.

Camera parts like sensor, viewfinder, operational buttons and dials, memory card and overall ergonomics change gradually without being able to reinvent the wheel a.k.a. camera. Real change comes in the form of software. For the majority of people. For the minority? Most likely only a dwindling selection of camera makers will survive in the long run. The CaNikon duopoly will survive, albeit ruffled. Best chances for a triopoly have Sony and Samsung with their focus on technology that’s dominating modern-day photography.

Olympus and Fujifilm? As much as I like their products, I wouldn’t bet my money on them. They bet everything on high-end mirrorless in attractive packages. But honestly, say what you want about the redundancy of the importance of sensor size and performance catching up with DSLRs. To speak with Thom Hogan, mirrorless cameras like the X-T1, E-M1 and A7(R) are low volume products at too high a price for the benefits they provide (and negatives they have).

Hogan goes on:

Cameras are still mostly executing the same old “disconnected box that takes photos on removable media” game (…) If I were running a Japanese camera company, I’d move the indicator to DEFCON 2 right now and be looking for a Silicon Valley company that understands imaging software to purchase and help with what will eventually have to be a full rethink at the camera end.

Well do I agree with Hogan? Conditionally. Digital photography is software driven. But isn’t Adobe struggling? The future lies in integration. Problem is camera makers are no software companies. That’s why RAW and TIFF are not yet phased out. They will over time with greater readout accuracy.

Nikon’s onto this dilemma since quite some time. In July 2013 its president Makoto Kimura was quoted as saying, “We want to create a product that will change the concept of cameras. It could be a non-camera consumer product.”

Nikon could have products in this vein released within five years, according to Kimura, who deflected questions on whether the company would develop a mobile phone.

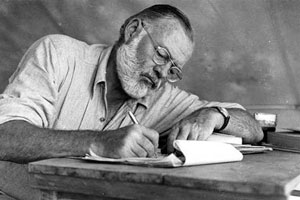

The smartphone is not the future of photography. Convergence devices and software integration are. The future of photography is all about data processing. For the majority. I’ll stick with the minority, metaphorically in the footsteps of Ernest Hemingway, author of For Whom the Bell Tolls, unforgotten for his camera-like realistic style of writing. Using simple, basic tools producing great output. The simplicity of his prose is deceptive. Yet Hemingway offers a “multi-focal” photographic reality. That’s the basics and all I ever want in a camera.