The full-frame debate is a topic I love to cover on THEME. There are no clear answers. On whatever side you’re standing, pros and cons are more or less evenly balanced. One of the beauties of today’s photography is the many options we enjoy. Each and every photographer finds an appropriate system, tool and style. It would be a ridiculous excuse for anyone to say, “Haven’t found my camera yet…” Still, the full-frame debate was a topic long ignored when cameras with Micro Four Thirds and APS-C sensor sizes established themselves as a sort of digital imaging standard for serious photography. Full-frame was out of reach for most. The topic is hot again with the ascent of affordable larger sensors with a 35mm film equivalence. Now Thom Hogan adds to the debate.

This article is a bit longish, and no, I don’t agree with honorable Mr. Hogan. But that’s dealt with at the end.

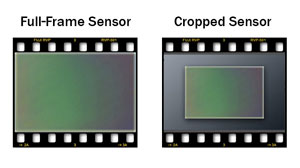

As a reminder, the most expensive part in a camera is the sensor. While full-frame sensors have come down in price, every time they do, a crop sensor should come down in price by as much as a factor of eight. Currently, a full-frame sensor can be manufactured for about $300. And the crop product is always less expensive.

And somewhere along the way, people got it into their heads that full-frame was so much better than anything else, that any time a company mentions that they’re coming out with another full-frame camera, especially an “affordable” one, the entire Internet gushes with lust over the newcomer.

Today, at least amongst the serious enthusiast market, there seems to be this growing groundswell of “I’ll be shooting full-frame some day,” says Hogan. This chorus grows with each new rumor or announcement of a full-frame camera. If you look around, he says, you’ll even find rumors of Fujifilm, Pentax and even Olympus eventually having a full-frame option or two.

Hogan:

One has to ask: what’s the big deal about full-frame? Why are all the makers taking scatter shots at the full-frame market and why are all the enthusiasts so fast to endorse this strategy? A cynic might say: because they’re hoping you’ll bite into a more expensive treat. If your unit sales are dropping 15% but you can get 20% of your top end DX buyers to purchase a much more expensive camera, your actual sales numbers might be okay.

Camera manufacturers love full-frame. It’s like reinventing digital photography for the broader mass market. Full-frame, I conclude from Hogan’s comments, will make us buy more expensive cameras and new and more expensive lenses.

That’s okay, explains Hogan, because you’ll say full-frame is better. Technically, yes that’s true in some measurements, but are you sure it’s actually better in practical application for you?

Hogan goes to great lengths to assure us that 99% of people reading this can’t see differences in color depth, 95%+ can’t see the differences in dynamic range, and the only way most of us will see the difference in ISO handling is if we push to an extreme.

Fair enough, Thom.

Now, there is a difference in depth of field capability. All else equal again, you can get a one stop shallower depth of field out of the full-frame sensor for the same shot if you’ve got the right lenses. Easy to see the difference. But how many of us actually need or use it?

This is where things get tricky. Really tricky. The minute I want more depth of field in certain situations, the cropped sensor (DX) starts to equalize very quickly with the full-frame (FX) camera. That’s because to keep the exposure the same, I have to up the ISO on the FX camera because I also have to use a smaller physical aperture. The amount of light available isn’t different.

Technically, the FX camera is going to be better but some small margin. It tests better in the deep pixel quality tests, it can shoot into light about a stop lower in light than the DX camera, and if you have a fast enough aperture you can isolate the focus plane more dramatically than DX.

But if you’re going for the same exact shot with both cameras, sometimes the FX and DX cameras are literally about the same! You boosted the aperture and ISO on the FX camera to match the depth of field on the DX camera while keeping the action frozen.

Plus, if you’re coming from any body more than about three or four years old, a new DX camera is going to be significantly better than where you were, too, so don’t judge DX on what you’ve been using. It’s really easy to see that in comparing D300 versus D7100 images, for example. Sensors came a long way between 2007 and 2013. More and better pixels, with gains pretty much across the board.

In fact, plus you have double pixels now:

- D7100: 24.2 bits color depth, 13.7 EV dynamic range, 1,256 ISO

- D300s: 22.5 bits color depth, 12.2 EV dynamic range, 767 ISO

The logic being: for most people, smartphones are good enough. Higher up the ladder, a whole slew of cameras would look like they’re performing at or near your “difficult to tell the difference” mark.

Hogan:

To me, this is an exciting time in photography. The Olympus OM-D E-M1, for instance, is above my “quality needs” bar (which is lower than my “difficult to tell the difference” bar, but not by a lot). It’s also small, light, versatile, and a joy to take on long hikes compared to my D4, which also happens to be 16MP. If I need 36MP in the backcountry, I’ll just stitch a couple of shots together.

Still, full-frame is what Hogan chooses for his professional work and what he picks up when he needs absolute maximum quality. That kind of reverses his analysis’ whole point, doesn’t it. Why not give us ordinary folk (who can’t see differences in color depth and dynamic range) the right to choose for ourselves.

The full-frame Hogan is talking about is a beast of the past. This generation’s full-frame is smaller, more compact, more versatile and equipped with sensors that suck in so much light and offer this depth of field leverage, well, if you have the choice it could be a shame to pick up an only marginally smaller camera with a fraction of sensor surface.

That’s the beauty of digital photography. It’s democracy in action. The empowerment of the masses.

I love shooting the OM-Ds and even point-and-shoots. But the larger the sensor and better the glass, the more three-dimensionality I seem to be able to extract on to the screen or a print by adding some fuzzy ethereal quality to the image that is difficult to achieve with smaller sensors.

You can’t verify this scientifically and it really depends on the quality of the glass. Fact is, the size of a sensor and quality of optics are closely related to the fullness or flatness of an image. Add the — hardly measurable — richness of light. There is light, and then there is light.

But, as Hogan says, it only matters for serious and paid work.

The only real remaining advantage of cropped or smaller sensors is the lens lineup, first and foremost if you’re a zoom lover. Especially Micro Four Thirds has to be applauded. Olympus and Panasonic deliver a system with lenses while Fujifilm’s X series prime lenses epitomize what photography with a good larger sensor is all about: best possible quality.

Full-frame, dear Thom Hogan, and this doesn’t diminish my respect for you, sir, is just an evolution of digital photography and doesn’t endanger the smartphone the least. On the contrary, it refers the cell phone to its place.

About the same size and weight of gear? Why isn’t this a no-brainer. Full-frame increases my photographic pleasures, and for those precious moments I’m more than willing to pay the camera maker quite a bit more.

Finally, we’re getting the gear that was always Leica’s right to exist.