I was sitting in a small local café in Addis which my friend and translator took me to. “This is the best place for coffee, and you know the world’s best coffee is Ethiopian.” Of course many countries make the claim for the world’s best coffee and I have heard it Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Kenya and Brazil. But I tended to agree with my friend. This dark black creamy Ethiopian espresso was a very smooth way to start the day of our field visit.

I had planned ahead a lot. As always, I read everything I could about the NGO I was working with, the country, culture and the specific issues. I knew my gear and was prepared for plan B and C.

Doing your homework is paramount to getting it right. You have to be prepared, which includes understanding potential security issues. With NGOs the assignment is often planned well in advance: who you’re interviewing, when and how.

Sitting there in Addis, sipping the espresso I was reminded that I am always a foreigner in most places on earth, disregarding of how many times I might have been to a country or how much I might know of the culture and language. Not that this disturbs me — on the contrary. It makes me want to know and learn more, because local knowledge and language is the key that opens the door to a person’s story and home.

So during the first day in the field I tend to see around a bit, get a feel for the place, get to know the translator, fixers and local NGO staff (if there is one) and gain my bearings. I do this to feel and sense the scale and characteristics of a location. To better understand the different layers of narrative that are hidden here.

With NGOs I often visit projects and clients who are beneficiaries of these projects, which means work for me starts with speaking to the people involved, and interviewing the client. If I am doing interviews and photography, I interview people in a casual conversational way, which can be an hour or two.

It’s a good start. It breaks the ice, builds trust and removes the awkwardness. It’s an approach that unlocks the story, an approach that rightly focuses on the people first. I might leave the camera to the side or just within reach, so that I am not staring down the barrel of the lens all the time, but actually built this relationship.

When taking images in my mind I start visualising my images. I don’t know how it happens, but I can just see what I need to photograph before I do. I look for angles, light, composition and subject matter to tell the story visually. Sometime that’s done in one image. Which is rare and perhaps the ultimate goals, but more often it’s the series that does it.

I tend to not interfere too much with what’s happening, trying to cover their day or work and just take the time to observe and get interactions, expressions etc. And sometimes I ask people about something they mentioned during the interview, something that reflects elements of their story.

I often leave people alone a bit, take a step back and starting photographing the surroundings and the environment to shift the focus. I then just happen to be there. This gives me unique angles where I am the fly on the wall getting shots, and expression that I might not get otherwise.

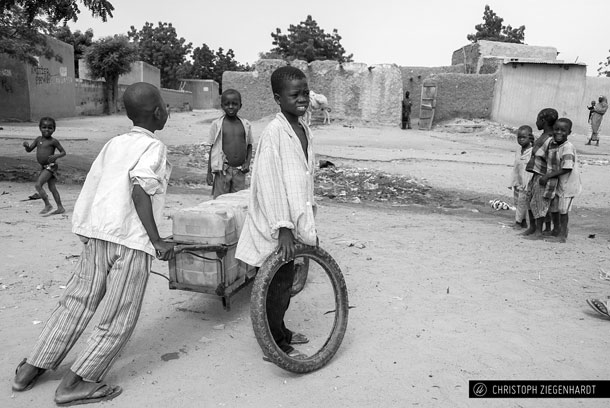

To me the ultimate challenge as a humanitarian documentary photographer is to document — and still be humane. To not just “get in there” to “extract” an image, but to connect, re-tell and compel through the visual.

I think it is a privilege to be in places and meet people that have gone through various hardships and difficulties in life or have special skills or abilities and to be able to take their photographs, tell their stories and make their voices heard a little louder.

I try to be sensible to the various discourses that exist in the media and in the development sector. And I need to find ways — in each situation — to not just overlay my ideas and agendas on the reality of a situation or a person’s story.

You know, documentary photography reminds us of the lived reality behind the abstractions of theory. But often all we see are the bad things, the corruption and poverty. But hidden within that, there is also the reality of hope, life, love and dignity. I think it’s important to show these different facets as part of the grander narrative.

Christoph Ziegenhardt is a humanitarian documentary photographer based in Melbourne, Australia. He shoots Nikon cameras and is a member of International Guild of Visual Peacemakers (IGVP).

He grew up in Nairobi, and his interests beside photography are in politics, current affairs, aid & development and journalism.

He enjoys a good political thriller and discussions over a beer or two.

See more of his work on www.christophziegenhardt.com and follow @czed on Twitter.