If you believe the hype, the next great technological frontier will be in the realm of vision, with digital tools embedded in glasses or in contact lenses to record, analyze and enhance what we’re seeing and doing. It’s called augmented reality. But some futurists have brought up another possibility, “deletive reality.”

After all, if you can add things to your field of vision, why not take them away? “If pedestrians in New York or Mumbai don’t want to see homeless people, they could delete them from view in real-time,” Ayeesha and Parag Khanna wrote on Slate last year, describing the potential of pixelated contact lenses.

In most American cities before the 1880s, the rich and poor didn’t have much of a window into each others’ lives. They lived, worked, shopped and played in different neighborhoods, which were arranged to minimize contact between social classes. It was much the same in other countries–especially in the mother country, England. The friendship and concern showed by Downton Abbey‘s aristocrats toward their servants is absurdly anachronistic. Real lords and ladies — even members of the rising middle class — aren’t likely to have known (much less cared) about the private lives of the poor.

Jacob Riis wasn’t the first photojournalist (others included the Romanian Carol Szathmari and Englishman Roger Fenton). But he was among the first to focus on the poor, using flash photography to great effect in his groundbreaking book How the Other Half Lives.

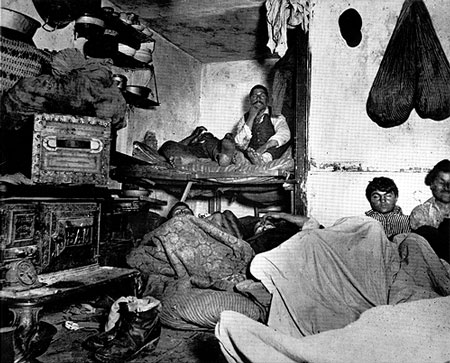

In 1887, the Danish-born Riis was working as a police reporter for the New York Tribune. Shocked by squalor and crime in the Five Points neighborhood, he was looking for a way to portray it viscerally. He tried sketching, but found he had no skill. Read about the new invention of flash photography, he immediately recognized its potential. With flash, he could patrol poor neighborhoods at night and take pictures of the inhabitants, unaware and unposed.

Ironically, though, this startled (or sleepy) look on his subjects’ faces gave Riis’s images a rawness and authenticity that made them influential. For the first time, New York’s “haves” got an intimate view into the lives of those less fortunate.

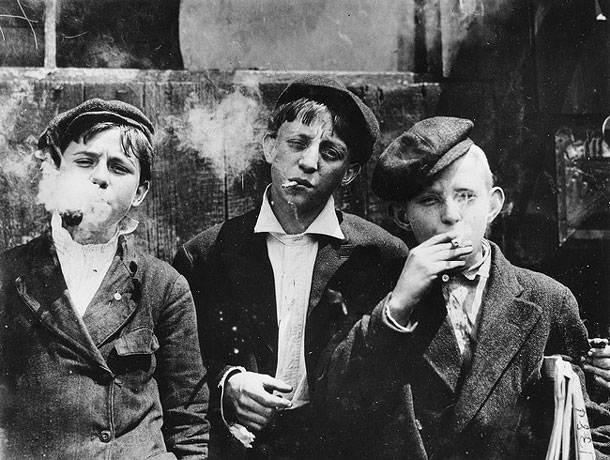

But Riis’s desire for social reform was motivated as much by disgust as by empathy. (How the Other Half Lives describes the Chinese as “sinister,” blacks as “sensual,” and Jews as having “a native instinct for money-making.”) It took another photographer, Lewis Hine, to make the next leap—into a socially aware photojournalism that was also empathetic.

This was a leap indeed. As Daile Kaplan writes in Lewis Hine in Europe: The Lost Photographs, “The appearance of indigent men and women in a ‘gentleman’s magazine’ might imply that some sort of relationship was called for between the reader (or viewer) and the person depicted: for a turn of the century nonprofessional, no such relationship existed. Until the emergence of the ‘social sciences’ the inclusion of such photographs in publications was seen as an invasion of privacy – not that of the people shown but of those who had to look at them.”

Hine’s rise as a photographer coincided with the emergence of Social Work as a field of study. His relationship with Paul Kellogg, a fellow student at Columbia University who became the editor of a progressive magazine called “The Survey,” was the key to his influence. Kellogg and Hine set out to create empathy for the poor, depicting them with delicacy and insight. Together, they took steps to reverse a prevailing mindset. Soon, looking at these kinds of images was no longer seen as an invasion of privacy. Instead, it was a moral imperative.

Could the next step be a “deletive reality” where, in addition to not having the face inconvenient truths in the media, we no longer have to see them around us? It’s a stretch, but maybe not a ridiculous one. In the New Yorker blog post Upgrade or Die, George Packer describes a present where things are getting ever better for the top classes, and worse for the underclasses. Combine this widening economic gap with technological breakthroughs, and it’s not hard to imagine a time when those with the means to do so could remove unsightly or troubling items from their field of vision.

This would be reprehensible, of course, and an ironic coda to the work of visual pioneers like Riis and Hine. But perhaps the doomsayers are being too pessimistic. After all, what technology taketh away, technology can also give back. So who’s out there working on an empathy app?