In the analog days this was a no-brainer. Had to work in low light? You pushed that Ilford to 800 or 1,600, knowing that the extra grain will give the shots that je ne sais quoi. You weren’t too worried about a print’s texture or too much grain. The onslaught of digital photography changed it all. Today even images shot at ISO 6,400 look perfect. Nevertheless, choosing the right ISO setting remains essential in digital photography. Not least to preserve that certain something.

Today there’s the dedicated button. You can alter the ISO for each individual shot — except, and that’s the big exception, when you shoot RAW. It is important to know that while a lot of settings can be changed when shooting a RAW file, ISO is fixed after the image is taken, so be sure to get it right! You lose dynamic range when you’re trying to push it.

It’s simple. Think of the RAW image as your film. Use the lowest ISO you can get away with.

Most of todays algorithms make JGP perfectly useable. Not that RAW files are a relict for pixel peepers — I shoot every paid job in RAW, just to be sure, you never know. But my guess is that in a few years JPG matches the output of RAW and TIFF making digital post-processing even easier.

But we’re talking ISO settings. Basically ISO is a burden of the past. The Nikon D800 and 5D Mark III make even ISO 25,600 perfectly useable — and there’s always a post processing fix. I’m using the Noiseware plug-in. You can’t go wrong with it.

Today’s sensors make it pretty easy to even use ISO auto mode. Still, when you go manual or override the auto settings you have to be aware of the impact on aperture and shutter speed.

Moving objects? Go for a faster shutter speed, but then again you might not want a perfectly well focused shot freezing the action. You might want the blur of a movement in your frame while the main silhouette of your subject is perfectly focused.

Say you maxed out aperture and have to go with a slower shutter speed. That may even improve your photography by adding the dimension of movement to your shot.

Naturally this allows a lower ISO setting = less noise.

If you need a higher ISO setting digital photography is a godsend.

For choosing the correct ISO setting ask yourself these questions:

- Is the subject well enough lit?

- Am I shooting in a “no flash” zone?

- Is the shot hand-held or am I using a tripod?

- Is the subject moving or static/stationary?

- And most importantly: Do I want a certain amount of noise/grain or a perfectly clean shot?

And beware, each metering method, a.k.a. center-weighted, partial or spot, gives you a different reading.

Key are the minimum shutter speed that you’re comfortable to work with and highest acceptable ISO for your specific camera. Meaning a D800 gives you much more leeway than a compact system camera. Know your gear. And know your shooting style and preferences.

There’s always a trade off — but less and less because today’s sensor technology allows you to shoot in most difficult light environment and still achieve respectable results.

Over time you will develop a feel for your camera, how it “likes” or “reacts” to what kind of light.

As a general rule: you want to avoid flash photography. Even at the cost of slight noise.

Experiment with and without flash. At least bounce the flash. The direct, uncontrolled explosion of light gives you harsh shadows and unwanted lines. But then again, experiment. Try the 2nd curtain sync flash (or rear/slow sync flash) and slower shutter speed (1/4 s or 1/2 s) for cool effects. You’ll love your party shots.

As a rule of thumb, keep the ISO at 200 or lower when shooting outdoors, and do your best to keep it under 1,600 when shooting indoors.

Use the lowest possible ISO setting when shooting images that you want to be rich in colour such as a beach scene with blue skies and deep blue water. Got ISO 50 coupled with a polarizer filter? Lovely.

Bottom line is: do not worry too much about a clinically clean, sterile JPEG or RAW file. Seriously, today’s sensor noise doesn’t look synthetic anymore and in many cases matches the beautiful grain of analog film. Fact is, noise has become barely noticeable.

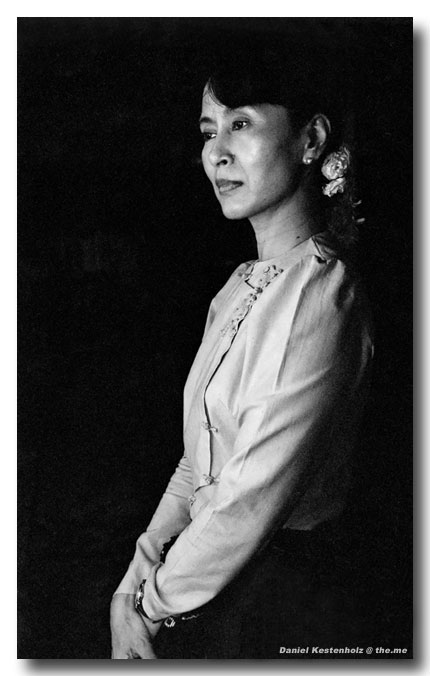

You don’t want noise in landscape, sports or architectural photography. But especially portrait photography loves a certain amount of noise. Grains adds a hint of timelessness, authenticity and documentary style.

There’s even the excellent DxO FilmPack simulating the film era by applying the quality, style, colors and grains of the most famous films rolls to your digital photos.

Here’s a portrait of Myanmar’s Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi taken a few years ago — not perfectly focused, harsh noise, blown-out highlights, oh well an Ilford 400 pushed to 1,600…