As suggested in a recent rant, the Net to a large extent consists of irrelevancy and narcissism. We’re mostly fed what we already know. What we’re served is hardly about relevance, but crude attempts to grab attention. An often pay-averse and bored digital bohemia decides what’s important. It takes some mastery to find one’s way through the oversupply of stuff that’s outright futile and simply doesn’t matter. On the other hand, the Internet can be highly productive and inspiring tool if one is able to sort the sheep from the goats. So here’s a kind of rant 2.0 — just imagine how the digital camera altered the way we photograph:

Things have changed dramatically within the past dozen years or so. At the turn of the millennium it was still a foolish privilege to have a serious digital cameras. The first capable digital Canons, Nikon, Fujifilms and Kodaks were dearly expensive, monstrous, underperforming and slow.

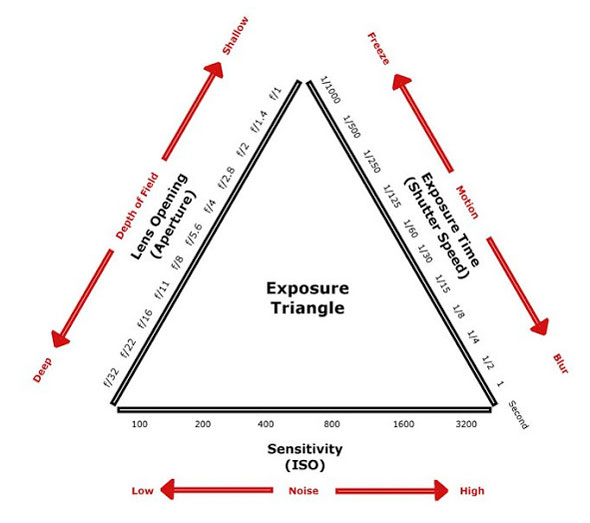

Film though quickly lost its appeal. The digital revolution made the photographer’s former trinity of aperture (depth of field), speed (motion) and ISO (sensitivity) look like boring child’s play. New cameras are computers offering a wide selection of functions and modes. In the end photography is still all about aperture, speed and ISO, yet our minds and eyes are diverted by the goodies these new multifunctional über-machines offer.

This has consequences on not only how we operate the cameras a.k.a. machines, but also on how we photograph:

- In the film days, I know a roll of film has 36 exposures and I have just so many rolls of film. Film is precious. I take my time to shoot. In the digital days, I enjoy virtually endless storage capability. The only limitation is how quickly I can operate the mighty beast. Meanwhile, so focused on a myriad of menus, functions and settings, I risk losing sight of what I actually try to be focused on…

- In the film days, the only menu offered is choosing the right speed and aperture. ISO is determined by the film used. When pushing a film one or two stops, well then the whole roll of film is pushed one or two stops. In the digital days, each and every exposure might have a multitude of corrective settings activated (against noise, for better dynamic range, tonal filters, etc.). It takes some practice to know what I really want in each occasion… Why didn’t I? I should have! Darn, forgot this…

- In the film days, I see a scene and I know exactly how to react with the camera. Because the camera’s settings are always the same. The camera is nothing more than an instrument to capture light. In the digital days, if not internalized through repetitive practice, practice, practice, that instrument with a multitude of confusing functions and settings risks becoming the center of attention, diverting the focus away from light, exposure, composition. Oops, just missed it again, the decisive moment.

- In the film days, I waste no time reviewing images. I stay focused while motives change. In the digital days, well, these cameras even have Web connectivity. I’m turned into a multifunctional being sharing everything instantly with the Whole Wide World (as if anyone would care)…

- In the film days, unable to review images, I turn my attention back to people and the surroundings when the camera is switched off. In the digital days, I keep on reviewing, guessing, trying, sharing, connecting, hell let’s start all over again!

- In the film days, even mom and dad smile for the camera. In the digital days, they’re slowly but surely getting sick of it. Not again.

- In the film days, if I ask a stranger for a group photo, I have to trust the person and select him or her carefully from other potential candidates able to handle a camera. In the digital days, anyone is able to take a picture. Yet I’m not pleased with the result. I review the photo and ask the person to take it again.

- In the film days, the inexistence of EXIF makes it a virtue to note down settings when shooting. The careful analysis after developing the film is a fundamental sine qua non to improve one’s photography. Everything goes in the digital days. Why care when I got hundreds of rolls of film on a single memory chip, allowing me to experiment, test and try. A few keepers per a thousand snaps, not a bad yield. Isn’t it.

- In the film days, after reviewing the developed images and carefully analyzing what can be done better, I have no other choice to improve my photography by improving my own skills.

- In the film days, the really fine work deserves to be printed, hangs on the walls and I enjoy it every day. In the digital days, the moment I post it, it’s lost on a timeline…

Conclusion?

Doesn’t mean one is not able to use the “film approach” with a digital camera. Yet it’s highly unlikely that most photographers ignore all the bells and whistles — and traps! — today’s digital cameras offer. If you’re able to find your way through the myriad of possibilities and know exactly what you’re doing, well then hail the digital revolution. Otherwise use factory settings. Switch off all those bells and whistles and bring to perfection what’s the essence of photography since its invention: the mastery of aperture, speed and sensitivity.

Set up the basics. Then ignore the menu. Get rid of the clutter.

If you still need in-camera processings, most of what can be set in-camera can be done later on the computer.

Slow photography, a.k.a. using your digital like a film camera, develops a feel for light that we usually ask the camera to do. Give it a try. Put yourself back into control. The camera is just a machine to control and capture light, and not the center of attention. It’s all very simple, really. And the more simple it gets, the easier we understand and master it.