German magazine Spiegel has an excellent interview with photographer Roger Ballen, a black-and-white film photographer for nearly 50 years who believes that he’s part of the last generation that will grow up with this media. Black and white, says Balen, is a very minimalist art form and unlike color photographs does not pretend to mimic the world in a manner similar to the way the human eye might perceive. Photography for Ballen has ultimately always been about defining himself — a “fundamentally psychological and existential journey.”

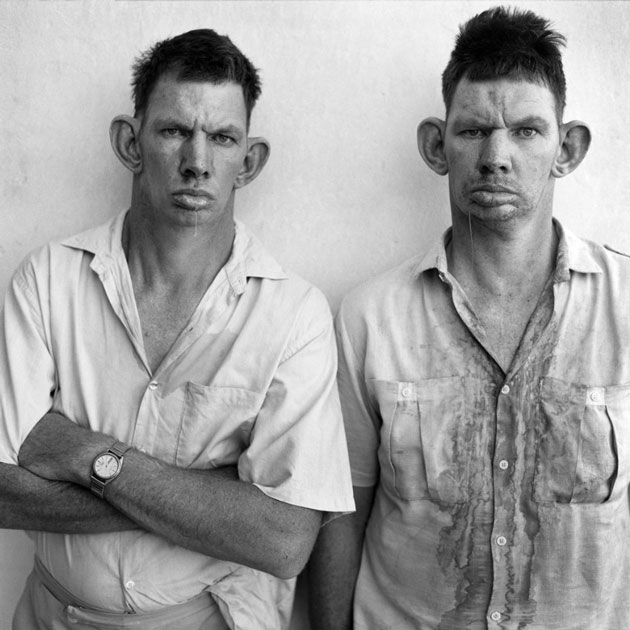

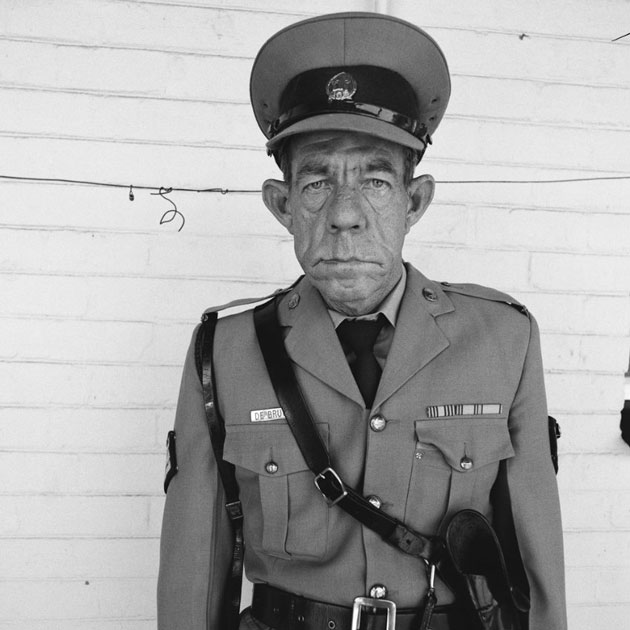

Ballen is interested in freaks, outcasts and the poor. He’s looking for his motifs on the fringes of society. Recently he rocked the boat with his video clip “I Fink U Freeky” below for Die Antwoord that made the eccentric band from South Africa world famous:

Here’s the interview:

Mr. Ballen, when you ask most photographers how they got started, they’re likely to tell you about their first camera. Is that true for you too?

No. My mother worked at the international photographic cooperative Magnum in New York, and then started a photo gallery. She had developed close relationships with several Magnum members and other photographers. She idolized and romanticized them — and her heroes were my heroes. They gave her lots of prints and photobooks, so I was surrounded by their images.

Who left the biggest impression on you?

Elliott Erwitt. He planted the seed for the humor that comes through in my pictures. Henri Cartier-Bresson also had a unique grasp on the decisive moment when a picture comes together. Paul Strand taught me a lot about perfect composition.

You also knew André Kertész.

He was an artist first and a photographer second. He and his work made me realize that photography could do more than document reality. Some of his most famous pictures were taken from his apartment on Washington Square in New York. I remember taking pictures from his balcony to emulate him.

You’re a commercial success, and that includes pop culture too. Your video for “I Fink U Freeky” helped put the South African group Die Antwoord on the map internationally. The clip has been viewed more than 33 million times on YouTube.

I knew the artists for many years. Seven years ago the vocalists contacted me and told me they identified with my work. Both of them, Ninja and Yolandi, sent some of their music videos. At first I didn’t know what to do with them because I wasn’t a video maker. Two years later, they came from Cape Town to Johannesburg, where I live, and I took my first pictures of them. In 2010, we integrated my drawings into one of their videos. It went viral, and that’s also when their career took off.

What was it like to direct “I Fink U Freeky?”

Our relationship is built on seeing eye to eye. They like the aesthetic I represent: strong, intense photographs that penetrate people’s psyche. All this is also relevant to their music. But it was real teamwork, and things just clicked into place: their music combined with my backgrounds and subjects that I have worked with for years.

When did you get into photography?

When I was 18 I finally got my first serious camera, a Nikon FTN. From 1968 to 1972, I studied psychology at Berkeley, and I did a lot of photography during those years. It was a pivotal time in the national culture, and Berkeley epitomized the counterculture. At the time, my work was quite socially and politically oriented, focused on anti-Vietnam protests and civil rights.

After you graduated, you moved to South Africa, which was still under apartheid. How does a Berkeley graduate arrive at such an idea?

I got to South Africa in a rather roundabout way. After five years of traveling the world and putting together my first book, Boyhood, I went to the Colorado School of Mines, and graduated with a Ph.D. in Mineral Economics in 1981. I didn’t find it easy to be in America at that time. I felt overwhelmed with the competitive and corporate nature of society. What I liked about South Africa when I first visited in the 1970s was that you lived as though you were in the First World but also had a lot of Third World around you.

But surely apartheid didn’t just pass you by?

ot at all. I felt the best way for me to make political change was through photography — my kind of photography. My book Platteland had a huge impact on South Africans’ perceptions of themselves. It showed white people who lived at the margins of society. It broke the myth of white supremacy. When it was published, I was subjected to a lot of accusations. I was considered a whistleblower like Edward Snowden at the time.

Does that make “Platteland” a primarily political book?

Not in my eyes. For me, the purpose of the book was to deal with aspects of the human condition as I perceived it. And that comes across to this day. The images in “Platteland” have meaning even to a generation in the United States and Europe that knows little about apartheid.

You have often described your photography as psychological. What do you mean by that?

For me, photography is a diary process, a way of marking my life and making my experiences permanent. Photos are like fossils to me. They help me come to grips with my passage through time.

(via Spiegel)