+++ BTW, we at THEME love to showcase your work. Don’t hesitate to contact us if you want to share your portfolio with others. No false modesty please!

Now here’s Lorenzo:

My gear back in 1998 was a used Nikon FE, bought in 1978, with the 35-70mm F2.8. Then I got myself an F100 and 24mm. Add a 80-200mm. So for my first assignment in Chile I had to carry a pretty big bag. Only in 2003 I found out that size really matters.

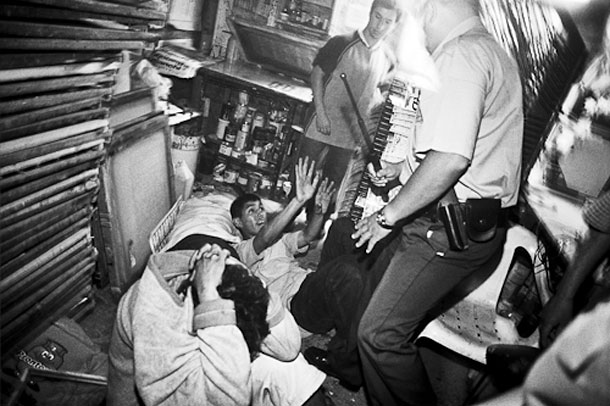

I was shooting in a Chilean police car and in jails. My gear was just way too big! I always loved Leica and wanted one, but couldn’t afford it. Then I came across the fantastic work of Luc Delahaye, Winterreise. And see, he was using a strange little black camera.

After some research on the Web I found out it was a Contax G2. I was lucky to find a used one in Santiago, with the three standard lenses 28mm, 45mm and 90mm. All my life changed.

I remember when I saw the contact sheet for the first time, I just couldn’t believe the details, especially in low light. That system blow me away for two reasons:

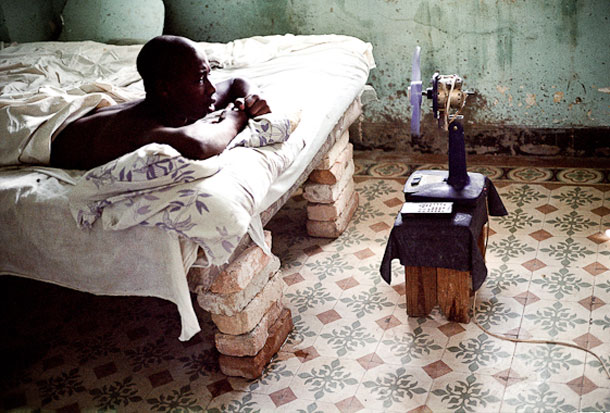

First, I could go wherever I wanted to with the camera around my neck. And boy do I love the 28mm and 45mm for portraits. I just didn’t look like a photographer. The Contax made me, in a way, invisible. So I was working on a book about a little town in the south of Chile, called Lota. It’s a former coal mining town now full of drunks and depressed people.

I couldn’t have gone there with the Nikon stuff, even with just the 24mm.

Very rarely I used the Contax with the 90mm, but anyway it wasn’t a pain in the ass to carry with me, so just in case I always brought it along.

I do remember an assignment back in 2005 for a Chilean magazine in Rio de Janeiro, inside a favela and about prostitution. I had a Nikon D200 and the Contax, but couldn’t stand the quality of the D200 files. So I just used the Contax.

Of course, later on I had to switch to digital completely. Films were hard to get and expensive in Chile. The cost of developing a role of film made me leave the Contax at home most of the time.

I was feeling like leaving a son at home. I could feel the Contax’s eyes looking at me, begging to take her along. I felt really sad I couldn’t use the camera anymore. I was always hoping for a digital Contax G3 to use with the terrific three lenses, but my hopes faded completely when it became clear that Contax closed down forever after more than a hundred years in business. That was a sad day.

Recently a friend asked me if I miss film. It’s a feeling of like being charged with electricity when going on assignment for two or three weeks, with 50 or 60 rolls of film and then coming back to see the contact sheet. Each time, it was like Christmas. But film is bad for the planet, my friend told me. He was from Greenpeace… I can see his point, but I miss film anyway.

So I was forced into the digital era. It might be a cleaner system for the planet. Maybe…

Then Leica came out with the M8, a really expensive tool, useless above ISO 400, recording images at a snail’s pace. But the lenses and the size brought me back to my Contax time. So I finally could get my hands on a used M8 in 2010, together with two Zeiss lenses, the 25mm F2.8 and 50mm F2. Thank God at least Zeiss was still in the market!

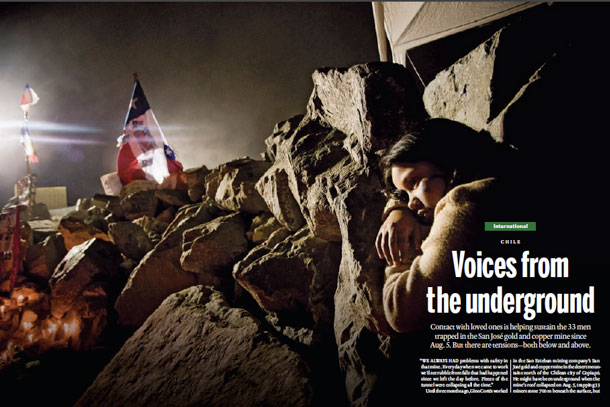

I brought the M8 with me when the 33 Chilean miners were trapped underground for two months. I was on several assignments back then and had the Nikon D300 as well. But everything published was shot with the Leica, even though I took three times as many pictures with the Nikon.

What Leica fans say about this system, that it “makes you think,” is pretty much true. Especially because you cannot take more than five to six pictures before the camera freezes. You just think twice before you press the shutter button.

Anyway, I think during the past three to four years many other brands discovered that size really matters. Look at the Micro Four Thirds system.

Fujifilm is doing a great job. In fact the X-Pro1 is basically a copy of the G2.

Now I have the D600 and am using it along the Leica M9. Nice cameras. Still, I just don’t feel that same “calm state of mind” as when I had the Contax, loaded with ISO 400 color film pushed to 1,600 or Kodak’s high-speed black-and-white classic, the Tri-X.

How it all started? I started to study the works of great photographers. I never took a technical photography course. I think it’s a waste of time. What I advise to those who want to start with photography is: buy a good camera and start taking photographs and analysing the great photographers. University taught me perseverance and discipline, and these have been very useful in my theoretical formation as a photographer.

In truth, the most important thing is observing the great photographic masters, develop one’s eye, seek inspiration… and also it helps to understand that the true photographer always goes back to old haunts, a concept expressed by many great photographers like Luc Delahaye, Paolo Pellegrin, Alex Majoli, Francesco Zizola and that I have experienced personally.

I also often photography the same places and same situations many times, in evolution so to say. Each time I return, I feel more invisible, arriving with my camera round my neck in situations in which previously it had not appeared possible to penetrate.

How I am able to capture moments of such spontaneous suffering or intimacy? Well from a practical point of view, I always look for someone in a place, and take heaps of time “working” on relations with the local people so they understand that I am not a classic photojournalist who has arrived to take photos for an agency.

One needs to have compassion to earn trust and above all, one has to mix with them with humility. Someone people trust, be it in a prison or in a slum, needs to introduce you. In general, I try to be with the people. I never go to posh hotels. If I have to stay in hostels I choose a small simple one to give the impression of being a humble person. And if it is possible, I eat and sleep with the people I want to photograph.

The point is that if I don’t deal with the human element, I don’t produce anything satisfactory. For that reason I don’t want to be involved in photography for agencies. For me photography is done over a lengthy period of time, and trying to go behind the headline news, to dig deeper here and there.

It is the emotion to enter with my camera, try to understand the psychology of the people, love them enjoy those moments. Many photographers are criticized for the fact that they only concentrate on the most extreme and tragic situations. It is true that in general, tragic photos sell better, and there are professionals who dedicate themselves solely to this aspect of the work. But sometimes they underestimate the traumatic effect of photographing certain situations.

Many photographers in contact with this type of reality end up profoundly scarred. The famous book, The Bang-Bang Club: Stories From a Hidden War, which documents the violence at the end of the apartheid regime in South Africa, cost the life of one of the photographers. He died from a bullet fired by a policeman — whilst another of the photographers who participated in the project committed suicide.

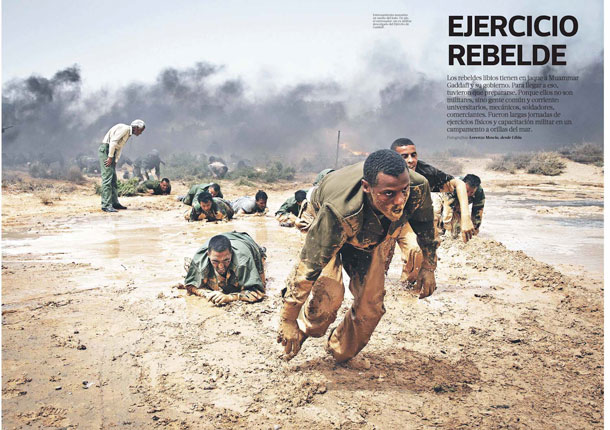

Personally, when I take these kinds of photographs, what moves me is a personal demand to test myself, to set myself a challenge, but also the fact that when I take photographs, I exorcise an image which in another way gets me under the skin. Apart from that, man has always been my favourite subject. It was natural then that man in violent situations would enter into my journey. A report I did about Haiti, for example, has not been easy. I needed long preparatory work to join military patrols. Photographing them has been a hard test. Personally I feel stimulated in this type of situation; putting to test my self-discipline, discovering where my limits lie.

My most crucial experience, however, was Easter Island. I lived there with the people, slept with them, immersing myself from head to toe. I am godfather to two children. I know things that tourists never see. Easter Island has been my springboard, my lucky break. In those times no one had yet photographed the island, apart from the beautiful landscape. An editor showed interest — what turned out to be a book. It’s called “Lights of Rapa Nui,” published in 2002, and can be ordered here.

Thanks to my work on the island, a Chilean tourist agency was interested in me and started to give me work. For a year I have worked with them. Later, they asked me to do more interesting things. I have gradually developed a network of contacts, have given exhibitions. Now I have two children, born in Chile. I love Latin America very much. Moreover, as it’s not very fashionable right now, photographic material is limited and if one knows the area a little and know how to move around, work can always be found.

So how do I manage to live in this work as a photographer?

It’s true that in photography it is very difficult if you are not well-known and accepted. One needs a solid base, and possibly other entrances. The ideal is to be able to work for a press agency, but it is very complicated work when you have a family, or even worse, a jealous wife… It is a work which requires lengthy absences, times in extreme circumstances. Since 2003, I have managed to make a living in photography. I work for various magazines. Apart from that I have to do photos for weddings, parties; that is what gives me a fixed income.

Then there’s my documentary about Cuba and another about Easter Island, rather political and complicated. A ten-minute version has won the 2006 Chatwin Prize. I am returning to my old passion of the documentary. The call is very strong. I like talking with people, filming them whilst they talk to me, assembling it, organizing and editing it.

I’m also working on a book about Lota, that small desolate former mining town in the south of Chile. It comes with a music CD composed by me.

My dream though is this: I want to make a grand trip around Latin America. A little like Che Guevara on a motorbike, bus or hitchhiking. To be with the people.

+++ For more on Lorenzo Moscia’s work visit his website www.lorenzomoscia.com.