By ALICAIR PELTONEN

By ALICAIR PELTONEN

B.D. Colen was walking his dachshunds in his Brookline, MA, neighborhood when he decided to return a phone call from his best friend from college, Bill Potter. Colen says he babbled for a bit with small talk before Potter finally got a chance to speak.

“So Colen, I just got out of the hospital,” he said.

“Oh shit, Potter, what’s the matter?”

“Oh,” Potter replied matter-of-factly.

“Stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung.”

B.D. Colen, a photographer turned medical reporter, turned back into photographer, knowing enough about medicine to try to convince his friend to go to Boston or New York City and be seen by a world-class specialist. But two weeks later Colen received another call from Potter, asking him to visit Seacoast Hospice outside of Portsmouth, NH. It was too late for treatment.

In his newspaper reporting days, Colen covered death with dignity, such as the AIDS epidemic, drug addiction and the famine in Somalia. He has written books on living wills and dangerously premature babies, and articles about assisted suicide. His first Pulitzer Prize nomination came in 1974 for a Washington Post series called “A Time to Die.”

Colen is no stranger to end-of-life issues, and maybe it’s a familiarity with death that makes it possible for him to so accurately capture life. So Colen did the one thing he knew how to do in response to his friend’s impending death: he pulled out his camera. Maybe it’s this familiarity with death that makes it possible for his photographic eye to capture life.

As a boy, Colen got a camera for his 12th birthday and ruined most of his first shots pretending to develop the film in the kitchen sink. Five years later he walked into the offices of the Westport Town Crier, his hometown newspaper in Connecticut, and announced he intended to become a staff photographer.

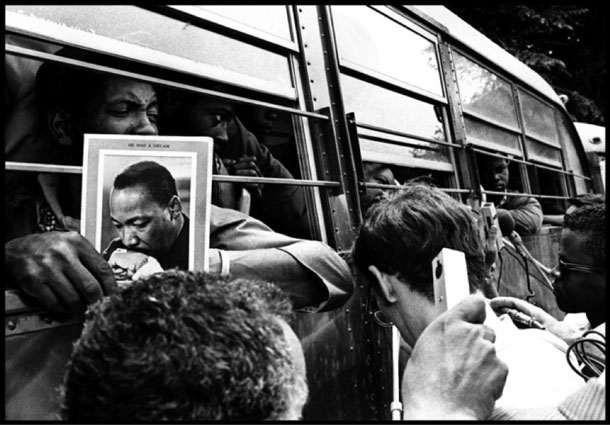

They agreed to give him $10 for any photograph they happened to use, mostly to make him go away. They owed him $90 by the end of the first week and hired him as an intern. It was later that summer in 1963 when the Town Crier sent him to Washington D.C., and the resulting front page headline read, “Our Man, 17, Marches on Washington.”

At George Washington University, where he and Potter met, Colen detoured into print journalism and began a 26-year run as a medical reporter at the Washington Post and Newsday. “I pioneered the coverage of bioethics in general interest newspapers,” he said.

Indeed, in 1984, Newsday recognized Colen and reporter Kathleen Kerr as leaders of their “Baby Jane Doe” coverage which won the paper a Pulitzer Prize in local reporting.

In 1993, Newsday sent Colen to Somalia to cover the devastating famine. “Somalia was just Mad Max,” he says, referencing the apocalyptic movie. “There was just nothing.”

The assignment rekindled his love of photography, and eventually he took those self-taught visual skills to a PR agency. It was at the Chandler Chicco Agency that Colen came up with the idea for his trademarked commissioned photography service called A Day in Our Life.

Not in these books: posed group photos or the glamour shot. “If you want to be Cinderella, I’m not your photographer,” he says. “Every photograph should stand on its own as a photograph. Whether you know the people or not, it should be an interesting image.”

Colen’s current day job is at Harvard as senior communications officer. Doug Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and world-renowned stem cell researcher, admits he often uses Colen as a sounding board.

In an email interview he said, “When I think we may have discovered something interesting or important, a discussion with B.D. is always helpful to me in trying to frame the issue for a broader audience.”

Melton has often asked Colen to photograph lab events for personal and public use. “I find his photos, particularly the black-and-white photos, to be unusually good.”

Colen’s daughter Alicia, a sales associate at the fine art photography Howard Greenberg Gallery in Manhattan, points to his years as a reporter to explain his talent. “He’s an observer, by nature. Not a participator,” she says.

Every once in a while someone will grab a shot of a full white-bearded Colen in his skull and crossbones bow tie, or riding his motor scooter. His own family photographs, however, seldom include him. Colen is usually behind the lens. “All of us have had cameras in our faces our entire lives,” Alicia says. “That’s just his way of participating.”

At the end of a week-long photography workshop he attended a few years ago, Colen snapped some photos of the master photographer, Eugene Richards, and his 14-year-old son. Going through the developed pictures, he noticed the shots of Richards. “I look at them and I say… this is what I do. This is who I am as a photographer. I document families,” he says.

The photos were proof positive for Colen that documentary photography didn’t need to be depressing. “It’s okay to not want to go shoot crack addicts or go get my ass shot off in Iraq. This is valuable.”

For Judy Revis — who has commissioned Colen twice — his photobooks are invaluable. Colen documented celebrations for Revis’ mother, Ida, on her 90th and 95th birthdays. “His ability to see the interactions and record them have become among our cherished memories. Yes, we knew he was with us, but not as a distraction; as a valued member of our group,” she explained in an email interview.

Colen produced a compilation book for each occasion. Revis hopes there will be a third for Ida’s 100th birthday, because, as she writes, the books helped her family “see where we had come from and perhaps where we were going next.”

On his way to visit his college buddy, Colen hit stop-and-go traffic and called the hospice center to let Potter know he would be late. He got Cynthia, Potter’s wife, on the phone. Potter had had a stroke at 8:30 that morning and wasn’t doing well.

When Colen arrived, Cynthia and his children were all there. After a while, Colen pulled Cynthia aside.

“Do you want pictures?” he asked.

After some consideration, she agreed.

The resulting set of images illustrates the emotional electricity that fuels a family saying goodbye. There are shots that portray tenderness as Potter’s children smile at their frail father and hold his hand.

There is sadness and concern as they tend to Potter’s comfort at what is clearly the end.

But surprisingly, there is also joy, as if a familiar story caused everyone to smile.