Horst Faas, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning war photographer who later was editor of the Associated Press staff in Saigon that produced the most haunting photographs of the Vietnam War, died on May 10, 2012, in his native Germany. He was 79.

Faas was the first photographer to win two Pulitzer Prizes. He began his front-line reporting at the age of 27 in 1960 the Congo, then Algeria. In 1962 he was reassigned to the growing war in Vietnam where he landed on the same day as Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter whom he often teamed up with to produce powerful and exclusive reports.

No one stayed longer in Vietnam, took more risks or showed greater devotion to his work and his colleagues than Faas, a leading member of the hardy and highly romanticized Saigon Press Corps.

“I knew how to take care of myself, to survive and to be able to take pictures,” Faas once said. “How to befriend people that I may need to follow and how not to be noticed. And how not to get in the middle of things.”

That, he said, is “the secret of all good conflict photography.”

“Don’t get between the groups.”

And yet his photographs often brought viewers close to the action.

Faas described his job in simple terms.

“I tried to be in the newspapers every day, to beat the opposition with better photos. I didn’t try to do anything grandiose. The photos were used and published and asked for, because Vietnam was on the front pages year after year after.”

“I lived from day to day, from event to event. It was a perfect story for an agency photographer.”

In Saigon he trained and mentored young Vietnamese photographers who idolized him as a surrogate father.

All journalists in Vietnam carried cameras. Faas created a suite of cameras and lenses for the reporters, and taught them how to use them.

“When in doubt, shoot everything at 500 at F8 and I will save you in the darkroom,” he joked.

The result was “Horst’s army” of young photographers who fanned out with Faas-supplied cameras and film and stern orders to “come back with good pictures” — and captured many of the war’s defining images.

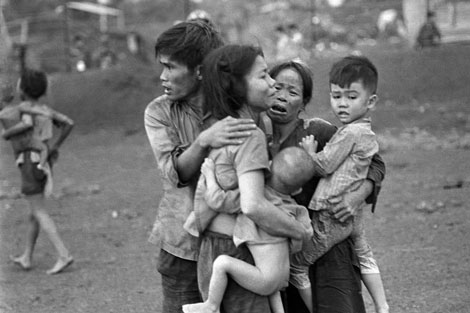

With his Teutonic humor and pudgy hands that constantly trembled, he still did it himself, turning out stunning photos that captured the helter-skelter, the fear and the pathos of war; his shot of a swarm of Huey helicopters delivering troops to the field almost includes the noise.

Though seriously wounded in a jungle rocket attack in 1967, he remained in what he called “this little bloodstained country” until 1973, shortly before the American military withdrawal.

As celebrated as his own pictures were, the photographs that came to be most closely associated with Faas were two that he selected, as an editor, for transmission around the world. Because of their graphic nature and the unwritten rules of conventional journalism, neither might have ever been more than a dot on a contact sheet in a drawer. Instead they became emblematic images of the tragedy of the American involvement in Vietnam.

The first, taken by the celebrated photographer Eddie Adams during a surprise insurgent attack on Saigon in 1968, showed a Vietnamese official, his pistol at arm’s length, executing a captured Vietcong soldier at point-blank range. The second, taken in 1972 by the Vietnamese photographer Huynh Cong Ut, known professionally as Nick, showed the aftermath of one of the thousands of bombings in the countryside by American planes: a group of terror-stricken children fleeing the scene, a young girl in the middle of the group screaming and naked, her clothing incinerated by burning napalm.

“The girl was obviously nude, and one of the rules was we don’t — at the Associated Press — we don’t present nude pictures, especially of girls in puberty age,” Faas said. Nevertheless, he set his mind on “getting the thing published and out.” The photograph won a Pulitzer.

“I don’t think we influenced the war at any time,” he once said. “I don’t think we helped to win it or helped to lose it. We didn’t work on the outcome of the war.” Making pictures about the suffering and horror of war, he said, was simply better than not making them.

He was co-editor of Requiem, a 1997 book about photographers killed on both sides of the Vietnam War, and was co-author of Lost Over Laos, a 2003 book about four photographers shot down in Laos in 1971 and the search for the crash site 27 years later.

+++ Also read Richard Pyle’s obituary, Horst Faas: A Last Hurra.