He was a class of his own: complicated, choleric, visionary, always borderline, conscious and breaking new ground. The movie director known for masterpieces such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Eyes Wide Shut and A Clockwork Orange rewrote filmmaking, often to the horror of his bosses. First and foremost though Stanley Kubrick was a photographer. He started off as a photographer, a heritage that always shone through later on when he became obsessed with the art of filmmaking. The purist-perfectionist couldn’t have made many of his movies’s scenes without his roots in the theory and practice of photography: creating an own reality, with idiosyncrasy being key. “You don’t try to photograph the reality,” as Kubrick once said. “You try and photograph the photograph of reality.”

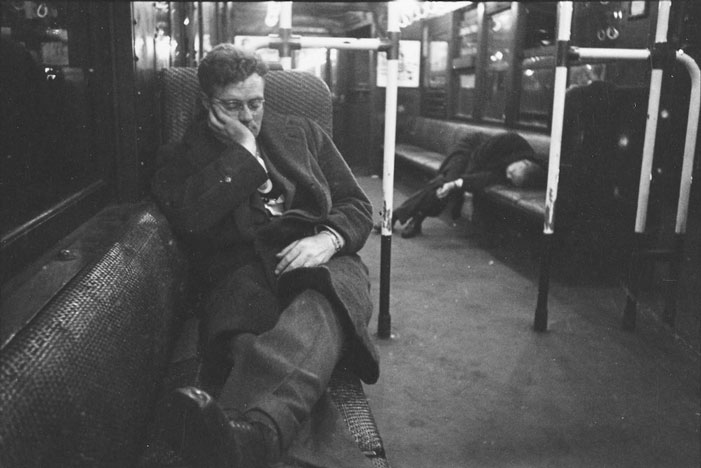

It was Stanley Kubrick, the street photographer. Even though back then he was just Stanley, the kid from the Bronx with an uncanny photographic sensibility. Kubrick often turned his camera on his native city, drawing inspiration from the variety of personalities that populated its spaces. Photographs of nightclubs, street scenes and sporting events were amongst his first published images, and in these assignments, Kubrick captured the pathos of ordinary life in a way that belied his young age. For more on Kubrick’s early photography work visit here and here.

From photographer to cinematographer — legendary filmmaker Kubrick was always fascinated by the art’s basics. That made him push the boundaries of moviemaking in many ways, and was responsible for some of the most enduring visuals in cinema. When he made Barry Lyndon in 1975, Kubrick shot with two ultra-rare Carl Zeiss primes, which had originally been created for NASA for use in the Apollo space program and were modified for Kubrick to use with a Mitchell BNC camera — which was also specially modified to accept the lenses.

Kubrick’s “understanding of lenses came from his stills background,” says camera pioneer and expert Joe Dunton. Kubrick collected many speciality lenses over the course of his life. “Lenses actually make the pictures,” Dunton says. “Lenses are the most important part of cinema picture making, which he understood very well.”

Among them: the Angénieux F2.2 12-120mm zoom lens that was the most popular in the world from 1966 to the early ’70s. This lens was essential to shooting in difficult natural light and often played a part in the director’s technically meticulous productions.

And then there were the magic Carl Zeiss 50mm and 35mm F0.7 lenses. Kubrick was able to film some scenes purely by candlelight. Carl Zeiss made ten of the F0.7 prime lenses in the 1960s, selling six to NASA, keeping one, and selling the remaining three to filmmaker Kubrick. The lenses were originally developed for NASA’s project aimed at taking still photographs of the dark side of the moon.

It’s difficult to talk about Stanley Kubrick without talking about his affinity for top-notch gear. He preferred to own rather than rent a bountiful collection of lenses, cameras and assorted gear. Here’s some background on Kubrick’s use of the modified primes:

Oh well, Kubrick’s famous 50mm lens lives on in spirit in the Nikon 1 32mm F1.2, a bit cheaper too! Both are similarly modified Planar lenses with an integrated condenser.

+++ For more on the photographer and cinematographer, visit the Stanley Kubrick Exhibition by the Deutsches Filmmuseum. The exhibition currently resides in Monterrey, Mexico. Next stations are Seoul and San Francisco. Highly recommended is the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, with comments from his colleagues and a narration by Tom Cruise.