One could argue that with arrival of the Canon EOS M3, the world’s imaging technology leader is finally taking mirrorless a bit more seriously, as suggested by Damien Demolder’s op-ed on DP Review. Right, that rather sounds like wishful thinking. The simple fact that the M3 won’t be available in the U.S. suggests the camera is neither a game changer nor a new mirrorless standard, but rather a bridge product between current and next generation mirrorless technology. For good reasons, Canon and the world’s number two camera maker Nikon don’t yet really see a need for a truly disruptive mirrorless system.

Demolder wants to see the opposite. “More, and soon,” he demands:

Canon really does need to go boldly here. These tentative measures just will not do. The compact system camera market will happen and grow whether Canon is on the bus or not. Now is the time not to bumble along, but to grasp the opportunity to make a statement, to have confidence and to carve a determined slice of the action. The EOS M3 might be a step in the right direction and a decent start, but it isn’t a system and it won’t win any wars on its own.

Or could it be, as Thom Hogan suggests, that the war over mirrorless interchangeable lens camera (MILC) technology is already over and the battle lost?

I think that both companies think a bit like I do: they believe that it will take something disruptive to restart growth in camera sales. The difference between me and them is this: I think I know what that disruption is and they don’t. Moreover, if I’m right about what the disruption needs to be, both Canon and Nikon are poorly equipped to create it, as it will mostly differences in software, not hardware, that define future cameras from present ones.

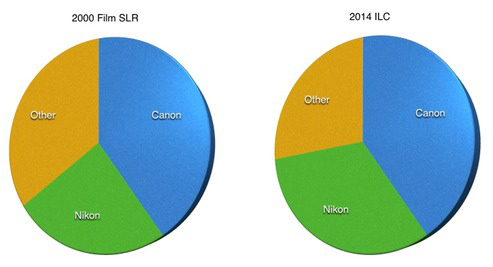

The last grand disruption, as we all know, was the iPhone. Or was it? Hogan’s pie chart says it all:

Canon’s share has stayed roughly the same overall, Nikon’s share significantly grew in the digital era by a whopping 30%, mainly because they were a first and aggressive mover. So, Canon and Nikon don’t really feel like aggressively moving into mirrorless whereas Other brands have lost market share since 2000.

In fact, these Other brands have changed their lens system and created whole new markets, says DP Review forum socialite HappyVan, costing their old customers a lot of aggravation. Sony left their Minolta customers behind, ditto for Olympus. Fortunately for Fujifilm customers, their former Nikon mount assured their lenses could still be used on Nikon cameras.

Canon and Nikon are “simply rising and falling with the water level,” writes Hogan:

If they switched (and could switch) all of their DSLRs into mirrorless cameras, its somewhat unlikely to provide them with an upside in terms of sales. The primary upside to them would be the one that Sony is currently enjoying: lower costs in producing the product — though Sony is giving a lot of that back by being aggressive in pricing.

So, the market’s verdict for now is that the MILC systems are no better than DSLR. So far mirrorless hasn’t caused a significant market disruption at all. But that’s not the future. It’s highly likely that at one point Canon and Nikon offer a true market disruptive technology that will have to be smaller, faster, cheaper and more profitable.

Their economies of scale will simply devastate the Others, probably with Sony being the exception that proves the rule. For now, as much impressive advancements MILCs offer, CaNikon put true power and performance into their easily upgradeable DSLRs/ILCs. A new switch, slightly better specs, and you have a whole new model. Soon a $500 DSLR camera will enjoy a once top end, 51-point AF system able to capture birds in flight. Which mirrorless does?

Power and performance are not the only important parameters. But especially Nikon’s complete upward compatibility, enjoy DSLRs while they last.