By BRIAN SWEENEY

I’ve put together another article, this time on the C-Sonnar. “Once upon a time” optical engineers wrote books aimed at photographers wanting to understand more about the instruments that they use. They actually explained things like “focus shift” and “spherical aberration.” I’ve tried to apply lessons learned from Carroll Bernard Neblette (Photographic Lenses, 1965) and Rudolf Kingslake (Lenses in Photography, 1951) to the C-Sonnar. I’ve seen focus shift discussed in forums, but not really explained.

The Zeiss C-Sonnar 50mm F1.5 (eBay) is the modern incarnation of Ludwig Bertele’s super speed lens designs of the 1920s and 1930s. The C-Sonnar faithfully reproduces classic Sonnar rendering that makes it a popular choice for portraits, and maintains a compact form factor popular for candid photography.

Before his famous Sonnar of 1931, Bertele worked for Ernemann (Krupp-Ernemann Kinoapparate AG) and developed the “Ernostar” F2. This lens had five elements in four groups, an asymmetric 1-1-1-2 configuration, eight air/glass interfaces. Ernemann merged with Zeiss, and Bertele created their most famous lens of the 1930s by filling in the space between the 2nd and 3rd element of the Ernostar with low index of refraction glass.

This reduced the Sonnar to six air/glass interfaces, improving transmission by almost 10%. The rear doublet used in the 5cm F2 Sonnar was split into a triplet, and the 5cm F1.5 Sonnar was born.

The modern 50mm F1.5 Sonnar is a six element in four groups design, a 1-1-1-3 configuration. It is the lens that Bertele would have designed if he had multicoated glass available; no need to get rid of the two air/glass interfaces using the “filler element.”

Used wide open, the image is dominated by light coming in at the shorter focal length of the edges. This is responsible for the lower-contrast/spread-out depth of field of the Sonnar used wide open.

Stopping down the aperture eliminates contributions from the edge; the image that remains is the product of the longer focal length center of the lens. It “shifts” towards infinity.

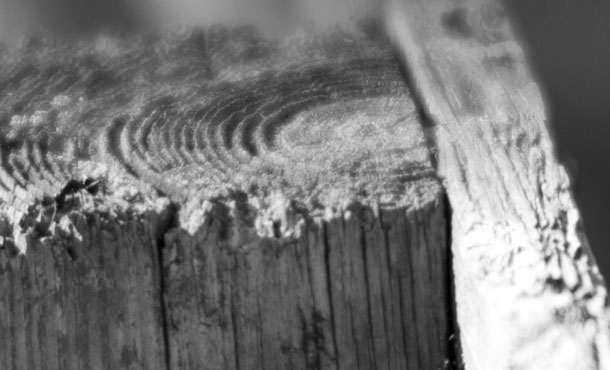

The next three images taken with the C-Sonnar on the M Monochrom illustrate focus shift when stopping down from F1.5 to F4. The point of focus is where the fence slat meets the post, the lens is optimized for F1.5 and the actual focus agrees with the camera.

At F4, the point of best focus is shifted about 1.

5” behind the rangefinder. To compensate when used stopped-down, back the focus off from infinity ever so slightly from what the RF indicates. This will require a bit of practice, but is well worth the effort.

Zeiss has taken full advantage of modern lens design in producing the C-Sonnar. It shares the 50mm focal length and F1.5 maximum aperture of the 1932 Sonnar, but uses larger diameter glass elements to reduce vignetting.

The C-Sonnar uses 46mm filters are used in place of the 40.5mm filters of the classic Sonnar. Geometric distortion visible in vintage Sonnar images is almost eliminated with the C-Sonnar. Field curvature readily visible in classic Sonnar images is greatly reduced.

The aperture ring uses 1/3rd f-stop clicks, with f-stops evenly spaced. The original Sonnar did not use click-stops, and had a geometric progression for stops. The spacing between f-Stops became much closer as you stopped down.

The modern C-Sonnar retains the 0.9m minimum focus distance of the original Contax camera, but has a short-throw of 90 degrees going from minimum focus to infinity. The Contax RF of the 1930s rotated 270 degrees for the same range, and the Leica mount Sonnars of the 1940s required 180 degrees.

The aperture of the C-Sonnar is shaped to offset focus shift produced by spherical aberration. The aperture mechanism of the original Sonnars stops down in a traditional circular pattern. The 1950s Carl Zeiss Sonnar stops down using a star-like pattern.

This “counter-intuitive” shape lessens the effects of stopping down on focus shift: light from the inner and outer portion of the star-like shape contribute to the image, extending the depth of field and reducing focus shift.

The modern C-Sonnar uses the star-like pattern of the 1950s Sonnar. In actual practice, the circular aperture produces smoother bokeh but does produce a more dramatic shift in focus and contrast when stopping down from F1.5 to F4.

“Value for the money,” the C-Sonnar competes with the recently introduced M mount 50mm F1.5 Voigtländer Nokton Aspheric and used Leica pre-aspheric 50mm F1.4 Summilux. If you are all about the sharpest image possible, other lenses are available. The C-Sonnar was made to a different set of rules.

I’ve recently been using the C-Sonnar on the M Monochrom, and have used it for two years with the M8. The C-Sonnar is center-sharp, which works out well on the 1.3 crop sensor of the M8. The classic rendering of the C-Sonnar makes it a perfect choice for the M Monochrom. M8 images were taken using an IR cut filter. M Monochrom images were taken using an orange filter.

See more of Brian’s photos in his album on LeicaPlace.

You might also not want to miss Brian’s excellent lesson in history Nikkor-SC 5cm F1.5 — The Lens That Brought Attention to the Japanese Camera Industry.