This story serves as a reminder to what great length early photographers went. Well the equipment was not exactly portable. Some of the early photography pioneers would risk their lives for a good picture. In 1900, the Kolb Brothers founded the first Grand Canyon studio and took some spectacular pictures. They dangled over slopes and searched out ethnic groups living in isolated locations. But it was an even more reckless action that took the brothers to stardom: a 101-day boat trip through the canon. The brothers’ motto: “If I capsize, I’ll keep shooting.”

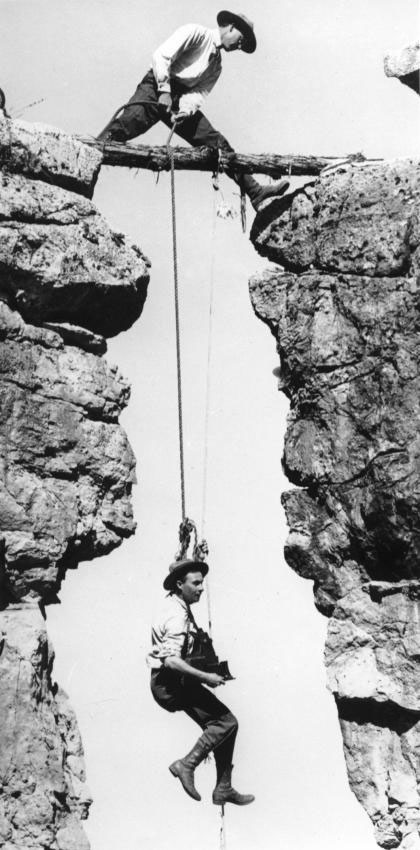

Whilst photographing the Grand Canyon in 1904, Emery Kolb’s life literally hung on a rope. The rope was attached to a tree trunk which spanned two rock faces. His brother Ellsworth stood on the trunk. He slowly lowered Emery and waited for him to press the shutter button of his large plate Graflex camera so he could pull him up again.

There is a photograph of the scene. The picture shows the two men and the rock formations against a cloudless sky. Emery and Ellsworth Kolb used this pose again and again, not just in 1904. The image appeared on promotional cards, souvenir books and posters. Very understandable. It shows them the way they saw themselves, as the conquerors of the Grand Canyon.

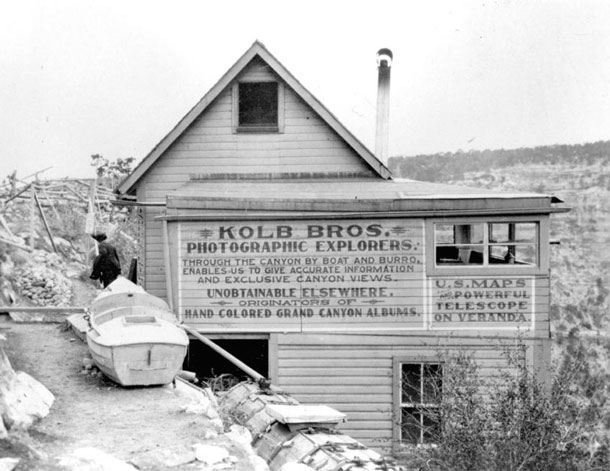

Even today, anyone traveling along the southern rim of the world’s largest canyon will stumble on the brothers’ the log cabin. It stands on the edge of the gorge and offers a panoramic view of the valley. Right here it becomes clear what so fascinated the two Pennsylvanians about the canyon that they repeatedly risked their lives to shoot stunning pictures — and eventually became almost as famous as the canyon itself.

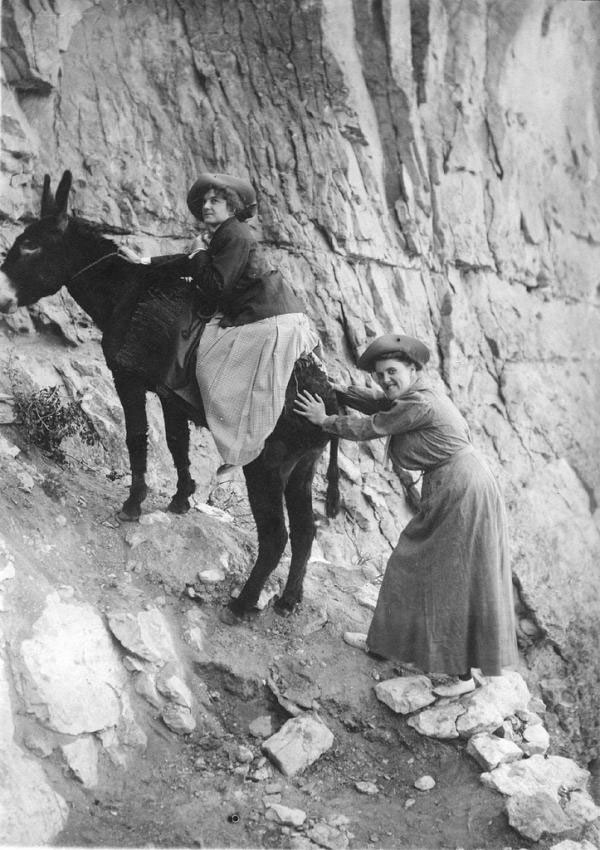

Photo Shooting on Mules

In Arizona, where the northern half of the Grand Canyon is located, there is a saying, “You can’t miss the abyss.” It is just too big. Without a doubt the sheer size of the Canyon is impressive. The gorge is some 450 kilometers long and 1,800 meters in depth in some places. The Colorado River runs along the bottom. The river current has carved its way through the rock layers over millions of years. There are small, winding paths leading down to the river bed and also many undeveloped areas, mainly in the northern part of the park, which should not be accessed even with good climbing equipment. The canyon walls gleam reddish brown, pale pink or even purple, depending on the sun’s position, a spectacle that attracts more than four million visitors annually.

The Kolb brothers could not resist the fascination of the Canyon. Ellsworth, the adventurer of the family, was keen to explore this natural phenomenon. He came to Arizona in 1901, a year before his brother Emery, at a time when tourist development in the area had only just begun. A few months earlier the Santa Fe Railway Company had completed a rail track to the park. Visitors were no longer reliant on carriages, they could take a train. The Canyon became a popular attraction for day trippers — and a romantic setting for courting couples.

In a sense the Kolb brothers were at the right place at the right time. Emery, the younger of the two who had taught himself the art of photography, joined Ellsworth who was working as a bellhop in Arizona. They opened their first photo shop in Williams, 60 miles away Canyon, where their main subjects were bar girls. They earned very little from their work. That changed when the eloquent brothers persuaded businessman, Ralph Cameron, to build a studio on his property located on the Canyon’s southern rim.

The new studio was right on the Bright Angel Trail. This was a particularly popular route to get to the Colorado River. The reason: for a one dollar fee tourists could cover the 14 kilometer route on a mule. As a result, there was a constant stream of visitors at Bright Angel Trail. Among the tourists were celebrities such as President Theodore Roosevelt who readily posed for the Kolb brothers.

No Electricity, no Water, no Darkroom

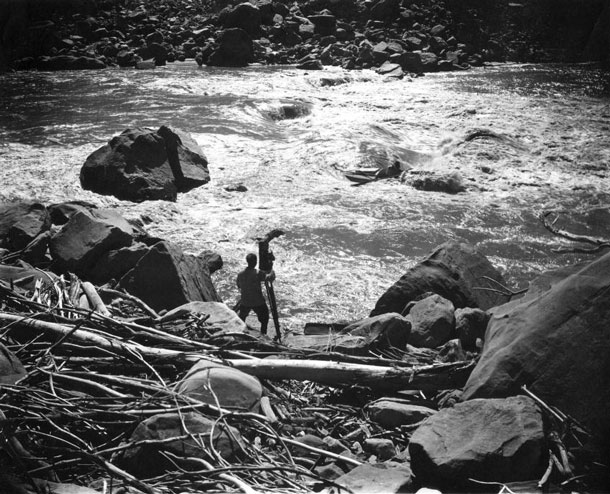

Every morning, Emery placed his camera in front of the toll barrier to take photographs of the tour groups. There was enough time to develop the pictures while the visitors made the long journey to the valley. This task demanded great creativity: at the beginning of the 20th century there was no electricity, water and certainly no darkroom at the Canyon.

In the first year the brothers lived in a tent which let in too much light so they developed their pictures in a disused mine. They used sunlight instead of light bulbs to dry the glass plates. The developing tank posed the greatest challenge. The plates had to be cleaned during the process but clean water was scarce. The Santa Fe Railway supplied the surrounding hotels with drinking water, the Kolb brothers, however, were left empty-handed. They only had use of the Indian Garden, an oasis on the Bright Angel Trail which was just below the photo studio.

Consequently the brothers built a darkroom of wood in the Indian Garden. Each day Emery would run five miles down the gorge, develop the photos on the spot and then run back up the track before the tour groups returned.

Folklore for Canyon Visitors

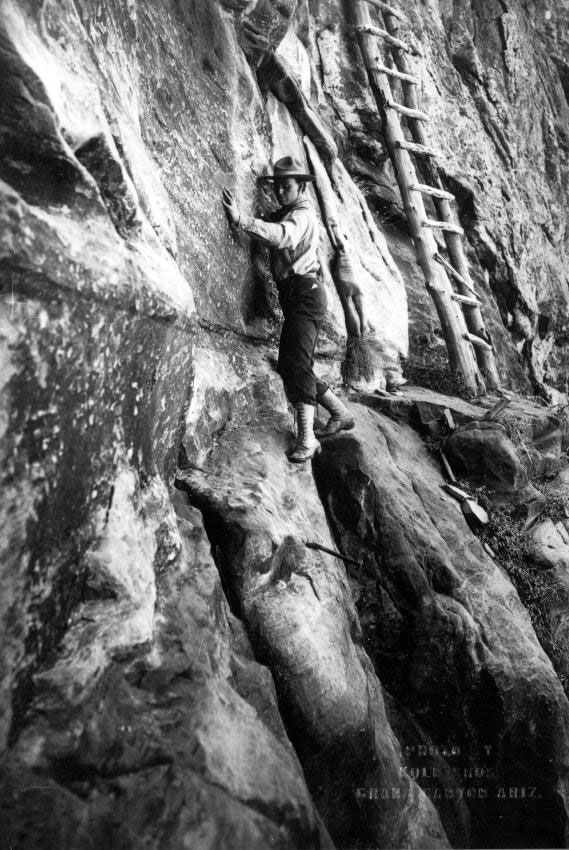

Not every visitor wanted a portrait of himself with a mule as a souvenir. The Kolb brothers therefore explored little known areas of the canyon on the look out for interesting subjects which would sell well. They followed craggy gold mining trails or Native Indian tracks. Their heavy photographic material was transported on the backs of their mules. Often the path ended abruptly and the brothers had to climb the rest of the way, the bulky camera equipment always with them.

They penetrated the habitats of native tribes. They got to know the Havasupai Indians and, for a small compensation, they were allowed to photograph the families in traditional dress — suitable folklore for canyon visitors.

Emery, the businessman, was satisfied with photography, but Ellsworth wanted to shoot more than just postcard views. He envisioned a real adventure trip: a ride on a boat down the Colorado River, a total of 1,200 miles, from Wyoming to California. It would be their “big trip,” a great journey with spectacular pictures was what Ellsworth hoped for.

The idea was met with little enthusiasm on Emery’s part. He considered the journey too dangerous, especially because he — unlike his brother — had a wife and child to take care of. In addition, the trip was nothing new. Emery knew of other men who had already traveled a similar route by boat and came back with photographs. He wanted to make the trip only if it were advantageous for the studio. There was only one solution: they had to make a film. Moving pictures of the rapids had not yet been made.

“If I Capsize, I’ll Keep Shooting”

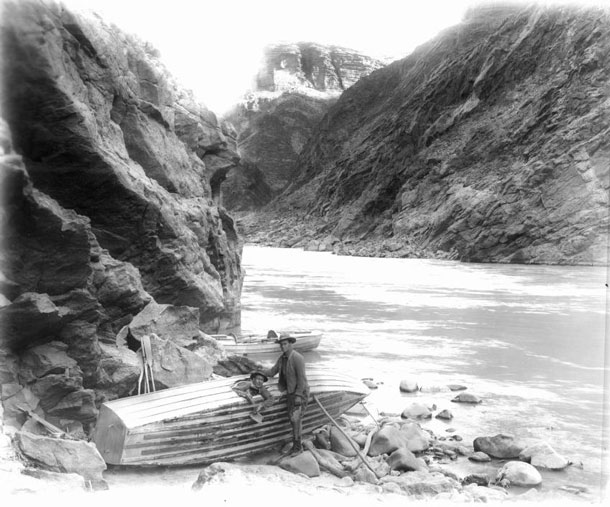

Preparations for the big trip dragged on for almost a year. The brothers had special flat boats made so they could navigate through shallow water. They also equipped the boat with special compartments to stow their equipment — the film camera, the celluloid film reels, other cameras.

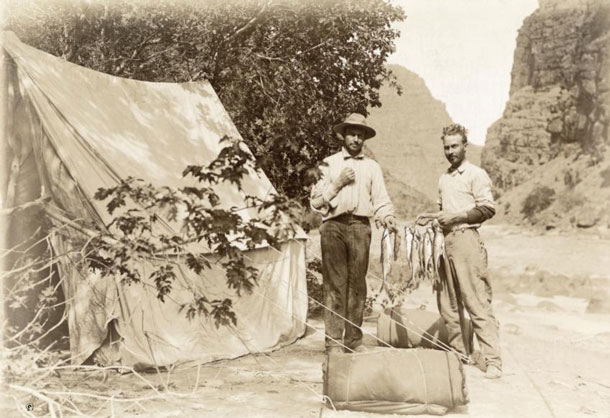

It was only in November 1911 that Emery and Ellsworth could start out. The train took them and their luggage up to Wyoming. From there they left for the Green River, a tributary of the Colorado River — their home for the next 101 days. During this time another brother, Ernest, ran the photo studio business. They slept on mattresses on the river edge, fed on fish and traveled through the canyon always aiming to make impressive movie images. Ellsworth said to his brother before they navigated some dangerous rapids: “If I capsize, I’ll film it first.” Saving himself came second.

Although boat and film camera capsized repeatedly and the equipment constantly had to be dried out, they finally had enough material for a half-hour movie.

Two National Heroes Tour the USA

The two brothers had very modest plans for their documentary work: they wanted to show the film, for a small entrance fee, at the Forestry Protection’s administrative quarters. The authorities rejected the request because the Grand Canyon was soon to be declared a national park and commercial events were considered undesirable.

This refusal was the best thing that happened to Emery and Ellsworth. They decided to take their film reels on tour. They traveled to the East Coast, portraying their adventures to politicians and scientists. Over time, they became the John Waynes of the documentary: they molded the public image of the wild, dangerous west just as Hollywood movies would do in future.

At a performance in Boston the two brothers attracted the attention of Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone. He introduced them to the President of the National Geographic Society and made sure the August 1914 magazine issue was dedicated to a large extent to the “big trip.” The article immediately transformed the Kolb brothers into national heroes. Ellsworth later wrote a book about the cruise. The novel became a best seller.

Emery, meanwhile, returned to his studio. But he no longer had peace and quiet: visitors now not only wanted to see the Grand Canyon but also to be photographed by the famous photographer, Kolb. The film made him famous. Emery showed the film every day until his death in 1976 as a reminder of how he and his brother had beaten the Grand Canyon.

+++ A pleasure to watch, here’s the movie of the Kolb brothers’ Grand Canyon boat trip: Grand Canyon Film Show, Narrated and Produced by Emery Kolb..

(translated from Der Spiegel: Berühmte Grand-Canyon-Fotografen: Fotosessions zwischen Himmel und Hölle)